By Henry Blodget

Over the past few decades, the US economy has undergone a profound change.

This change has helped rich Americans get richer. But it has also contributed to growing income inequality and the decline of the middle class. And, in so doing, it has fueled populist anger across the political spectrum and slowed the growth of the economy as a whole.

What is this change?

The complete embrace of the idea that the only mission of companies is to maximize profit for their shareholders.

Talk to people in the money management business, and they’ll proclaim this as a law of capitalism. They’ll also cite others, including the idea that employees are “costs” and competent managers should minimize these costs by paying employees as little as possible.

These practices may help boost stock prices, at least temporarily. But they aren’t actually laws of capitalism.

They’re choices.

Not long ago, America’s corporate owners and managers made different choices—choices that were better for average Americans and the economy. They also had a profoundly different understanding of their responsibilities.

“The job of management,” proclaimed Frank Abrams, chairman of Standard Oil of New Jersey, in 1951, “is to maintain an equitable and working balance among of the claims of the various directly interested groups… stockholders, employees, customers, and the public at large.”

By paying good wages, investing in future products, and generating reasonable (not “maximized”) profits, American companies in the 1950s and 1960s created value for all of their constituencies, not just one. As a result, the country and economy boomed.

Over more recent decades, however, this balance has radically shifted.

The stagnation and bear market of the 1970s contributed to the rise of shareholder activism, a trend immortalized in the 1980s by the fictional corporate raider Gordon Gekko in the movie “Wall Street.” In that era, American companies had become bloated and complacent, and they needed a kick in the ass. “Greed is good,” Gekko declared, firing smug managers and restructuring weak companies. And the nation’s beleaguered shareholders justifiably cheered.

But 30 years later, Gekko’s shareholder revolution is still going strong, and the pendulum has swung too far the other way. Urged on by a vast and hyper-competitive money management industry, American companies now increasingly serve a single constituency — shareholders –while stiffing employees and cutting investments in future products.

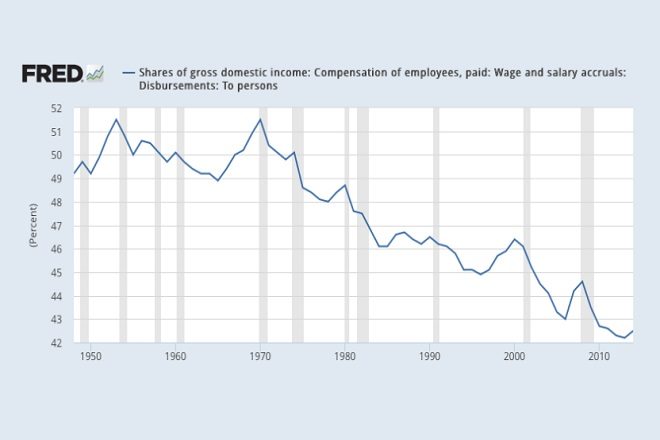

The most salient illustration of this is the divergence between profits and wages.

Corporate profit margins have been rising for 15 years and are now near their highest levels ever. Corporate wages, meanwhile, have been declining for 4 decades.

Nor are these the only ways that the “shareholder value” religion has warped our economy.

The richest 1%’ of Americans now own nearly 45% of all the country’s wealth, near the highest level since the "Gilded Age" of the 1920s, with an average net worth of $14 million in 2013. Meanwhile, the average wealth of “90%-ers” has plunged in recent years to just above $80,000, the same level as in the mid-1980s. Millions of Americans who work full time for highly profitable corporations earn so little that they're below the poverty line. The bottom 50% of Americans own nothing.

Beyond fairness and decency — the ethical decision to share more of the economic value a company creates with the people who devote their lives to creating it — the problem with the profit-maximization obsession is that it hurts the economy.

Why?

Because wages and investments at one company become revenue for other companies.

Consumers account for about 70% of the spending in the economy, so our spending is what drives economic growth. Most people work, so another name for most consumers is “employees.” And except for the richest Americans, most of us spend almost everything we make.

When we are paid less, we have less to spend, and economic growth slows. When we are paid more, we spend more, and growth accelerates.

Consumer spending also drives business investment. When consumers are flush, businesses invest aggressively to meet demand. When consumers are strapped, however, companies sit on their cash — or just hand it to shareholders.

buy clomiphene online buy clomiphene online no prescription

Amid today’s already weak demand, companies are exacerbating the problem by cutting investments and increasing dividends and stock buybacks.

To be clear: There’s nothing necessarily wrong with some hedge fund managers making $500 million a year — or a presidential candidate being worth a self-reported $10 billion. Capitalism is the best economic system known to man, and the “profit motive” helps drive it.

The problem is that when capitalism is practiced the way it is today, wealth becomes so concentrated that much of it doesn’t get spent. (Billionaires can hire only so many service providers and purchase only so many cars, houses, and islands.)

Economists cite many factors that have contributed to the rise of profits and decline of wages over the past few decades — globalization, the “skills gap,” the decline of unions, the loss of “high-paying manufacturing jobs.”

These trends are real, but they obscure the real cause: Company owners are choosing to maximize short-term profit by paying their employees as little as possible.

It's time for a more balanced approach.

(--Henry Blodget is the CEO and editor of Business Insider --)

The article can be viewed here

Opinion: Time for a better capitalism