Promoting Access to Decent Work Amidst Sri Lanka’s Economic Crisis[1]

From IPS’ flagship publication, ‘Sri Lanka: State of the Economy 2022’

- Access to decent work opportunities in Sri Lanka is limited. Even when jobs are available, not all workers have the same access to decent work. Only 20% of the working-age population have access to formal work.

- Access to formal employment is much lower than the overall average for females, low-skilled workers, and youth.buy lexapro online http://iddocs.net/images/layout4/gif/lexapro.html no prescription pharmacy

It is also slightly lower for old-age workers and rural sector workers.

- To fuel economic growth and become more competitive in the global labour market, Sri Lanka must increase its stock of highly skilled workers through improved education and training, and create more professional and managerial job opportunities.

- Investments in economic sectors likely to generate more productive jobs will couple economic growth with job creation.

- The legal, social, and infrastructural barriers that prevent women from accessing decent work should be addressed to improve female access to the labour market.

The Decent Work Agenda

The Decent Work Agenda was launched by the International Labour Organization (ILO) in 1999 with the primary goal of promoting “opportunities for women and men to obtain decent and productive work, in conditions of freedom, equality, security and human dignity”. Decent work is also a critical component of Goal 8 of the 2030 Agenda on Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), which encourages inclusive economic growth that is not harmful to the planet.[2] The Decent Work Agenda provides a solution to the problem of growth being exclusive (as opposed to inclusive) as improving access to decent work will ensure access to adequate wages, social security and safeguard human rights.

This brief examines the gaps in access to decent work in Sri Lanka and suggests policy recommendations to overcome the disparities, mitigate the downside impacts of the current economic crisis, and support recovery efforts.

Decent Work in Sri Lanka

A large share (62.3%) of household income in Sri Lanka is earned income according to the Household Income and Expenditure Survey (HIES), 2019, conducted by the Department of Census and Statistics (DCS). Of this, 37.5% was from wages and salaries, 18.1% was from non-agricultural activities, and the remaining 6.7% was from agricultural activities. This signifies the importance of access to decent work for reducing income inequality in Sri Lanka. During economic setbacks, issues like income inequality get side-lined and receive less attention amidst other priorities. The current crisis highlights the importance of adequate wages and social security to withstand economic shocks. The COVID-19 pandemic also exposed how informal workers were the most affected by adverse economic shocks.[3] Moreover, it is harder to target those in the unorganised informal sector to provide relief, as policymakers have little or zero information on who they are and their needs.

Gaps in Access to Decent Work

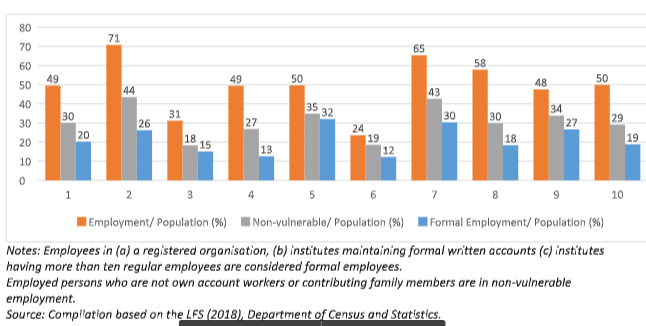

Access to decent work opportunities in Sri Lanka is limited. Even when jobs are available, not all workers have the same access to decent work. The best available measure of decent work is formal employment. Formal employees, by definition, are non-vulnerable workers whose employer contributes towards a provident fund on their behalf. According to the Labour Force Survey (LFS), only 20% of the working-age population is in full-time formal employment (Figure 1). Like other measures of decent work, access to formal work also varies substantially across population groups. Those who are educated have the highest access to formal work, followed by prime-age workers. The youth, females, and those with low levels of education have the least access to formal work.[4] Access to formal work is also slightly lower for old-age and rural-sector workers.

Figure 1: Access to Different Types of Employment

Trends in Employment-intensive Growth

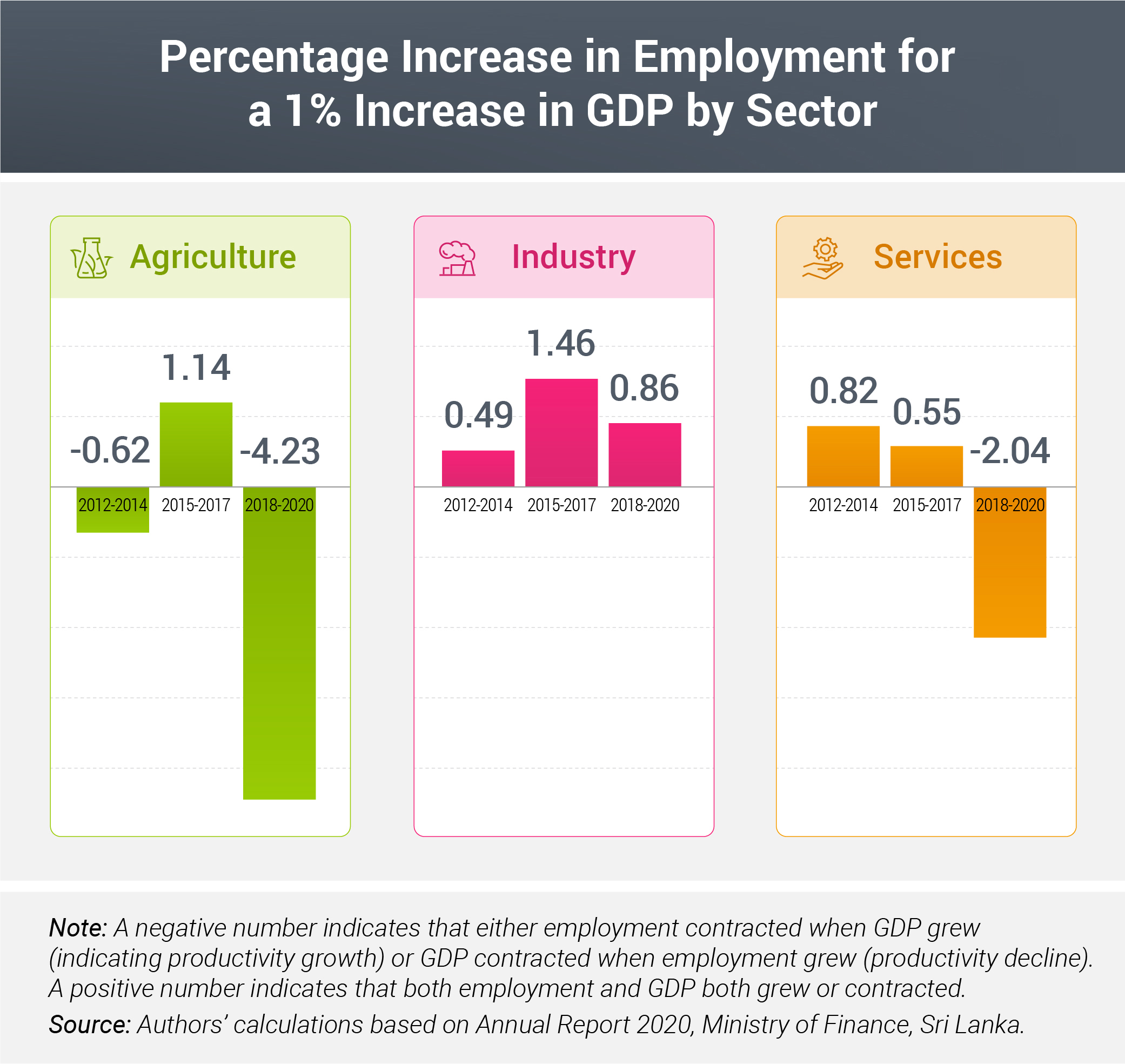

Goal 8 of the 2030 Agenda calls for inclusive and sustainable economic growth promotion that supports full and productive decent work opportunities. The main way of achieving this goal is by investing in sectors that are more likely to create productive employment. Growth in such sectors is more inclusive, as the benefits of growth are shared through employment income. The arc elasticity of employment – the percentage increase in employment for a 1% increase in the gross domestic product (GDP) – assesses how employment expands relative to economic growth. Sectors that create more jobs while increasing productivity which boosts access to higher-paying jobs, is one aspect of decent work. For productivity to increase while expanding employment opportunities, both employment and value addition in the sector must increase, and the growth in the latter must exceed the growth in the former.

The infographic depicts the trends in arc elasticity of employment in the three major economic sectors in Sri Lanka during 2012-2020 in three-year intervals. In the 2018-2020 period, only the services sector showed productivity growth, and unlike in the previous period, employment contracted by 1.5%. It indicates a decrease in access to productive jobs in this period. The decline in labour market conditions was mainly due to the Easter Sunday bomb attacks in April 2019, followed by the COVID-19 pandemic, which saw economic conditions in the country sharply deteriorate. During this period, employment opportunities moved from the industry and services sectors to the highly labour-intensive agriculture sector. According to LFS, 2020, 91.4% of agricultural workers are informal workers who are not covered by social security.[5] Their average monthly earnings were lower than those of workers in the industry and services sectors. This indicates that labour market conditions have regressed from the Decent Work Agenda, with labour moving to the less productive and lower-paying agriculture sector, where social security does not cover most jobs.

Workplace Discrimination

Demand-side factors such as occupation segregation, wage gaps, and discrimination in the workplace too affect workers’ access to decent work. Occupation segregation occurs when working conditions and hours are more attractive to certain types of workers. For example, occupations such as construction and transport are more attractive to males. The framing of existing labour legislation in Sri Lanka is paternalistic; it operates on the premise that females need to be protected through regulations which require employers to provide special privileges when hiring females. Further, in Sri Lanka, employers bear the cost of providing maternity benefits to female workers. Such regulations make employing females costly for employers. As such, they may show a preference for hiring males over females, thus reducing female access to decent work.

In addition, the traditional attitudes and social norms on the roles and responsibilities of males and females play a role in female access to decent work. Most firm-level policies on employment are made by bodies where female representation is either non-existent or minimal. Thus, the needs and requirements of females are rarely considered in those policies. As can be seen, these social norms are considered by employers when making decisions on recruiting female workers. A recent International Labour Organization (ILO) study found that some managers were unaware of the implicit gender biases in firm-level policies and practices.[6] One example is the requirement to work excessive hours beyond the legislated maximum. Such policies are more challenging for females as their families’ primary caregivers, especially those with children.

Policy Recommendations

Increase the stock of highly skilled workers through improved education, training and investments, and create jobs for skilled workers: With rapid technological changes, new jobs emerge while conventional jobs become obsolete or drastically change. As many of the remaining jobs require high-skilled workers, future job growth and opportunities will likely be in high-skilled jobs. Hence, Sri Lanka must invest in creating high-skilled managerial, professional, and technical positions with a higher probability of sustaining access to decent work through education and training.

Invest in economic sectors likely to generate more productive jobs: Strategic investments to expand productive work can improve access to decent work. To increase sustainable access to decent work, Sri Lanka must invest in expanding sectors likely to generate productive employment and implement mechanisms to safeguard such sectors from adverse shocks. Such investments are more likely to be inclusive as economic growth benefits people through increased employment incomes.

Address barriers which prevent women from accessing decent work: A variety of factors ranging from the legal environment, social infrastructure, and social practices inside and outside the workplace hinder greater female participation in the labour market. Making labour legislation more gender-neutral, enhancing access to affordable and quality transport and childcare facilities, and regulations that reduce explicit and implicit discrimination in the workplace will improve female access to the labour market.

*This Policy Insight is based on the

comprehensive chapter “Improving Access to Decent Work” in the ‘Sri Lanka:

State of the Economy 2022’ report – the annual flagship publication of the

Institute of Policy Studies of Sri Lanka (IPS). The complete report can be

purchased from the Publications Unit of IPS located at 100/20, Independence

Avenue, Colombo 07 and leading bookshops island-wide. For more information,

contact 011-2143107 / 077-3737717 or email: publications@ips.lk.

[1] Institute of Policy Studies of Sri Lanka.

(2022). Promoting Access to Decent Work Amidst Sri Lanka’s Economic Crisis. Policy Insights. Colombo: Institute of Policy Studies of Sri Lanka.

[2] Decent Work and Economic Growth. (n.d.). Promoting Sustained Inclusive and Sustainable Economic Growth, Full and Productive Employment and Decent Work for All. Retrieved May 10, 2022, from Global Goals: https://www.globalgoals.org/goals/8-decent-work-and-economic-growth/

[3] Institute of Policy Studies of Sri Lanka. (2021). Pandemic and the New Normal: Sri Lanka’s Labour Market in Sri Lanka State of the Economy 2021. Colombo: Institute of Policy Studies of Sri Lanka. pp. 109-130.

[4] As a share of total employed, females in formal employment are higher than males in formal employment. However, as a share of the working age population, females in formal employment are lower than males in formal employment. This is because only 31% of females are in employment, compared to 71% of males.

[5] Department of Census and Statistics. (2020). Labour Force Survey. Battaramulla: Department of Census and Statistics.

[6] International Labour Organization. (2017). Breaking Barriers: Unconscious Gender Bias in the Workplace. Geneva: International Labour Organization.