By Jekhan Aruliah

We can be so blinded by the white hot heat of innovation that we fail to see the red embers of renovation. We are so focussed on finding treasure and riches in the bright new future that we forget about the jewels to be found in the dimmer recesses of the past. Not everyone makes this mistake. In the 1990s US companies chasing bumper profits took out patents on products of the Neem (Margosa) tree and of Turmeric. Some of these patents were overturned, with the Government of India successfully arguing they had been in traditional use in South Asia for thousands of years. The BBC reported in 2004 about a patent granted to a US company in 1995:

“India has won a 10-year-long battle at the European Patent Office (EPO) against a patent granted on an anti-fungal product, derived from neem”.

Proving these products and methods were common knowledge to our ancestors needs historical documentation. Other treasures too can be found hidden in the historical record. Traditional cookery recipes, health medicines, therapies, and doubtless other things waiting to be found by the most patient detectives and turned into profits by the most entrepreneurial entrepreneurs. Modern day management gurus love to quote ancient texts such as Tsun Tzu’s “Art of War”, Kautilya’s “Arthashasthra”, and more recently Machiavelli’s “The Prince”. Ancient wisdom is still applied in cutting edge companies today. The past isn’t dispensable.

The risk of losing the documents and media of the past is not only a threat to cultural heritage. The risk is also of losing valuable commercial, legal and practical knowledge.

That risk spectacularly and tragically became reality in Sri Lanka in 1981. When the Jaffna Public Library, one of the largest collections of Tamil literature in Asia with its collection of over 97,000 books and ancient scripts, was burned by elements from the South as the Sri Lankan Civil War was starting.

More precious items were lost during this war as people fled battles taking with them only what they could run with. Books, manuscripts and other materials some hundreds of years old were left to be destroyed in the fighting. Or after the fighting had moved on, to decay away in the abandoned rubble.

Wars start and they stop. There are other chronic threats that have lasted millennia and won’t go away: insects; mice; damp; floods; careless storage; careless heirs. Treasured collections passed down the generations are lost when the latest heir doesn’t have space or the interest to store the stacks of dusty boxes. The boxes are quietly put in the garbage or on a bonfire. Documents are used as table mats to protect commonplace wooden tables from coffee stains, or crumpled into packing to protect vases and glasses worth far less.

Noolaham was started in 2005 by a small group of Sri Lankan Tamils who were determined to prevent another traumatic loss like the destruction of the Jaffna Library collection. In the beginning they started making digital records of documents using simple digital cameras and scanners. Some documents would be read and typed into the computer. From these small beginnings Noolaham, now constituted as The Noolaham Foundation, has at the time of writing this article digitised 2.25 million pages.

Noolaham is creating a digital archive of the cultural, historical and political documents and other media of the Tamil speaking community of Sri Lanka. They want to make this archive accessible to all people Worldwide. Canada based Natkeeran L Kanthan, coordinator of technology at the Noolaham Foundation, said “Whatever we preserve, we seek to make available within a short period of time, respecting applicable copyrights. Digital Discovery and Access is a major principle/value for the Noolaham Foundation. The Aavanaham platform is a state of the art platform used by universities and organizations world wide. We make all material available for research for private study upon reference request free of charge”.

When I visited the Noolaham Foundation in Jaffna, I met their Chief Operating Office Mr.Somaraj Kulasingam. Somaraj was a user of the Noolaham data archive before he joined the organisation, in particular for the Tamil law books he used for his studies. Having worked for many years with OXFAM and UNICEF, Somaraj saw an advertisement in the press for a manager at Noolaham. He applied and got the job about one and a half years ago.

Before sitting down to talk, Somaraj gave me a tour of their offices based in an aging bungalow in Kokuvil north of Jaffna Town. Here they have shelves of printed material, including bundles of old newspapers carefully wrapped in brown paper, waiting to be scanned. They have computers and cameras and scanners, and a small team of volunteers and paid staff. While much of the digitization is done at these offices, they will often visit the owners of documents and scan them onsite. Either because the owner is unwilling to release their precious documents, or because it is safer to transport the team to the fragile document than move the document to the team’s office.

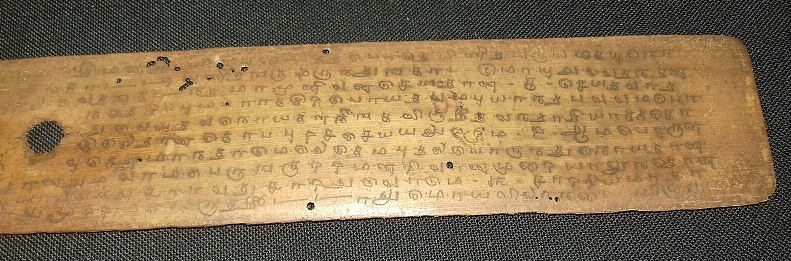

Sometimes the team finds literal treasure troves. A wonderful library of health related ola leaves was offered for scanning by a traditional medicine practitioner in Pallai. There are doubtless many collections like this that may not survive the current owner, to be discarded as junk during the probate process.

Noolaham also has a small space in the Jaffna University Library where they work scanning documents they find there. And Noolaham has teams of volunteers based overseas, who will scan documents and send to the Noolaham document repository.

Noolaham receives books from recycle centres, from libraries, and from private donations. Sometimes people will lend Noolaham documents to be scanned and take them back. Sometimes they will scan the documents themselves and email them to Noolaham. Noolaham welcomes scans of documents produced by people around the World, ideally at least 400dpi resolution, which can be sent by email to noolahamfoundation@gmail.com. If they receive a scan like this showing a particularly important document, Noolaham will try to make arrangements for a more professional digitization to be done of the document.

Somaraj said the volume of material has been startlingly large. They originally expected to have 30,000 ola leaves in their archive by now. They actually have twice that many. These ola leaves, some hundreds of years old, include Siddha Medicine, Astrology, Pranam (history of temples), and Manthirikam (magic). I put “Manthirikam” into Wikipedia to find out more, but only found an entry for an Indian film stating “Maanthrikam (lit. Magical) is a 1995 Indian Malayalam-language action comedy film…”. Apparently even Wikipedia had not yet found someone to post an entry for this. Some other old ola leaves are not being published yet because the Tamil script is archaic and so they need special expertise to understand what they are about and catalogue them.

As well as old documents, Noolaham is collecting modern material. This includes everything from printed texts to new media recordings and pictures. Noolaham also creates its own new material, taking videos of traditional trades and craftsmen.

CigarMaker: By By SL Trades and Crafts Documentation Project (user: Noolaham_TamilWiki) - Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=81741212

Shell Collector: By Thivasel - Own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=72801321

If you want to find pictures and videos about Cigar Making; Lime Making; Weaving and more click here: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/User:Noolaham_TamilWiki/Crafts_Documentation. Not only is it a fascinating set of pictures for the casual browser like me, entrepreneurs and academics may find inspiration here.

One key area is recording oral histories in which people are videoed telling their own stories. Some people are famous, some are very old, some tell the stories of disappeared and dying arts and customs. Speakers are nominated to Noolaham, who will go and visit them to make the recordings. Sometimes these chances slip away. Somaraj tells me of a time they went to meet a 90+ year old former folk dancer. On that day he was unable to speak, so they left only for him to pass away before they could return. Still, there are many others that have been recorded. For example this link will take you to the oral history of the dancer Sinnathambi.

To ensure against another massive loss like the burning of Jaffna Library, Noolaham has four backups: one in their office, one in a Jaffna bank vault, and two more in other parts of the World. Noolaham have received funding from the British Library in London for scanning ola leaves. The British Library itself will hold this collection, which in literary terms is as safe as the gold in Fort Knox. In due course Noolaham will hold a real-time backup on The Cloud. The chances of this archive will be lost, with its multi location backups is exceedingly small.

At the time of writing this article, Noolaham had digitised 2.25 million pages, including ola leaves, newspapers, and books. It had archived over 8,000 pieces of multimedia, and taken 300+ recordings of people giving their personal oral histories. Over the years more than 250 have volunteered their services, 500 people and organisations have donated funds, and over 1,000 have donated Tamil literature and other materials.

Funding comes from many sources. Mainly donations from Tamil organisations and individuals, but also from academic institutions such as the British Library. Costs are kept down by the hundreds of volunteers who have donated their time to the Noolaham Project. But Noolaham needs more funds. Natkeeran, came up with a list of services they can offer: Digitization; Digital Repositories; Recording Oral Histories; Documentation of current events. His list was longer than this. Natkeeran commented:

“Most of our funds come from small donations (10 pounds or 10 dollars) from many supporters. That is the community supported model we have now. We would like to strengthen by establishing a Trust with an endowment that will ensure a basic level of funding. Noolaham needs the following to grow and be sustainable

- Funds

- Community (Volunteers, Content Contributors, Supporters, Staff)

- Expertise & Technology

I asked Somaraj and Natkeeran what the plans for the future are. Their plans include the following:

- Currently able to digitize 40,000 pages, or 1,500 documents, per month. Want to increase this by three times. This will require additional funding for staff and equipment.

- Upgrade the technology used for storing the document and media from “cloud storage stack” to a “linked data discovery” platform.

- Establish permanent units in the East and Upcountry.

- Expand our field multimedia documentation (oral histories, photography, video documentaries) to cover non-textual, oral, visual and tacit knowledge bases

Noolaham has other plans to widen and deepen their offerings. And they want to undertake academically rigorous research projects using their library of material.

Noolaham has two websites which are open to the Public. Together they see over 33,000 visitors and 375,000 page views each month.

http://aavanaham.org/ is for new media, photos and recordings.

http://www.noolaham.org/, which is for texts.

Noolaham is not a commercial business, but it could be. As the Tamil Diaspora’s links to its homeland becomes generationally more tenuous, many would value creating a permanent link to their heritage. Noolaham could earn funds from the Diaspora making oral histories by their parents and grandparents and videos of their ancestral villages.

Noolaham is creating a mountain of information, an enormous cultural archive that is open to the public. For those with the talent to find and exploit them there are business opportunities hidden in Noolaham’s 2.5 million, and growing, pages of documents and its multimedia archive. For others, there are uncounted hours of fascination browsing through the libraries. Even for people like me who don’t understand Tamil just looking at the pictures and watching the videos is a delight.

To contact Noolaham you can email Mr. Somaraj at noolahamfoundation@gmail.com.

Further information is also available at The Noolaham Foundation’s website, http://noolahamfoundation.org

( — The writer Jekhan Aruliah was born in Sri Lanka and moved with his family to the UK when he was two years of age. Brought up in London, he graduated from Cambridge University in 1986 with a degree in Natural Sciences. Jekhan then spent over two decades in the IT industry, for half of which he was managing offshore software development for British companies in Colombo and in Gurgaon (India). In 2015 Jekhan decided to move to Jaffna where he is now involved in social and economic projects. He can be contacted at jekhanaruliah@gmail.com — )