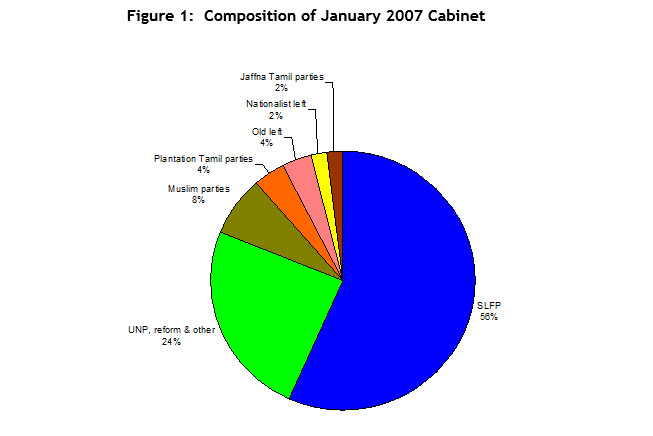

Source: News reports

Note: Party affiliations are per Supreme Court, and are subject to interpretation.

Is it good for Sri Lanka and its future? Each person will have to make up his or her mind, but here is my take, for whatever it's worth.

The test that I apply to anything political in Sri Lanka is a two-fold one: is it likely to contribute to restoring peace to this land and is it likely to contribute to economic reforms that will bring prosperity to its people?

If it passes both parts, it is good; if it passes none, it is bad; if it passes only one, it is not too bad and may be better than the norm. After all, we are in Sri Lanka, where under-performance is a finely honed art.

By this test, this political development is better than the norm.

But it is definitely better than the misbegotten, meaningless MOU between the UNP and the President that is being bemoaned by the international media and by those who should know better.

The only result of that particular MMMOU was blank-cheque approval of the budget by the opposition party and business as usual by the President.

This is a controversial position that requires some justification.

Constitution

We must begin from the 1978 Constitution, memorably described as the "bahubootha vyavastava" by the previous President.

The 1978 Constitution is a bad adaptation of the original republican, division-of-power constitution, the US Constitution that came into effect in 1789. The original stood the test of time much better than the bad copies: it has been amended only 27 times (actually even less, if one gets into the details) in its almost 218-year history.

The Sri Lankan Constitution of 1978 (and its proximate model, the French Constitution of 1958) have been amended 17 times in their much shorter histories. (Here, as with the party affiliations of the current Cabinet, ambiguity exists, but not enough to detract from the argument).

In the bastard versions, more so in Sri Lanka than in France, the real power resides in the Presidency. The legislature matters little; the parties even less. Of the judiciary, the less said the better.

Unlike in the original, the cabinet has to be selected from among sitting members of the legislature in Sri Lanka, violating the fundamental principle of separation of power between the legislature and the executive.

In the US, the President can take people from Congress to his Cabinet, but at that point they leave the legislative branch and join the executive. And he does take from the "other" party.

Bill Clinton's last secretary of defense, Bill Cohen, was a Republican Senator who resigned the Senate to serve on Cabinet; George W. Bush's secretary of transportation was Norm Mineta, a former Democratic congressman, who resigned from the House.

The absence of a fixed term for the legislature and the criminally abused power to dissolve Parliament are but two among the many reasons why the executive overwhelms the legislature in Sri Lanka.

In the early years, parties were able to maintain discipline because of prohibitions on cross-overs, etc.

However, under current Supreme-Court interpretation, there does not seem to be any way to remove an MP who violates party discipline.

This has exacerbated the sclerosis of the party system. The parties are far from democratic in their internal governance, so the apparent perversity of the Supreme Court may actually not be too wrong.

Peace

If one thing can be concluded from the sad history of this country since the breaking of the 1948 political compact with the minorities by the unilateral adoption of the 1972 Constitution, it is that, at minimum, we need a new constitutional arrangement that devolves more power to the Tamil minority living in the Northern and (parts of) the Eastern provinces than did any of the previous Constitutions.

The necessary (but not sufficient) condition to peace is, therefore, a new Constitution.

How does one get a new Constitution? Two-thirds majority in the legislature and a majority of the votes cast in a referendum, according to the 1978 Constitution.

Given the malign results of our one experience in extra-legal Constitution-making in 1972, one hopes fervently that it will not be repeated, however bahubootha the 1978 Constitution is.

Are we closer to meeting the constitutional requirement after the entry to Cabinet of the UNP reform group than on previous occasions when constitution making was or could have been attempted, such as 1998, 2000, 2003, etc.? Possibly.

Until 2000, the government did not have a complete draft of the "package" despite repeated and insistent demands for cooperation from the opposition.

They were being asked to sign on a blank sheet of paper, with the details to be filled in by the President later.

What the proposed referendum of April 1998 (cancelled when the then President got cold feet because of the Dalada bomb) was going to be on was a mystery. The package was not ready.

Much has been made of the bad behavior of UNP MPs in 2000 when the package was presented to Parliament, but neither they nor the TULF could have accepted a hurriedly cobbled together package that had many surprises, especially with regard to elections.

In 2003, the childish behavior of a faction of the UNP sabotaged any chances of winning the support of the President and her party for any constitutional reforms.

In retrospect, it appears that the strategy of then Prime Minister was to drag out the peace negotiations until the Presidential election that he thought was his to win.

The cohabitation of 2001-2004 was a classic opportunity to bring the two main parties together on a common platform to enact constitutional reforms. Both parties were weak and needed each other; the international environment was conducive and the ceasefire existed. But in early December 2003, with the collapse of the Mano-Malik negotiations, that opportunity too was squandered.

Now, in the second year of the six-year term of the President, the prospects for a 2/3rd majority are closer than ever before. And the components of a new Constitution exist in the flotsam and jetsam of previous constitutional reform efforts.

The current President has yet to demonstrate that he has the necessary understanding and commitment to provide leadership for the historic task of winning a majority of the votes cast at a referendum.

But, he is trusted by the Sinhala majority, more than his immediate predecessors as President and Prime Minister.

He passes the "who can be trusted to negotiate the fate of the Ampara district?" test with higher marks.

President Nixon, who was trusted by conservatives, was able to establish relations with China, and complete a liberal project that would have been almost impossible for a liberal President.

In the same way, the current President may be the one to convince the Sinhala majority to make peace with the minorities.

Despite himself, he may enter the history books that eluded his predecessors and win reelection for reason in 2011.

And with the concrete collaboration between the UNP and the SLFP led coalition starting with the appointment of the new Cabinet (in contrast to the MOU), it may be that this government is closer to a 2/3rd majority than any other since the fake 4/5th majority enjoyed by the Jayawardene government under the 1978 Constitution.

The fact that this gargantuan Cabinet includes pretty much all the parties except the extremist ones, and has seven minority representatives (14%) within it is also a positive factor.

Therefore, on the first part of the test, the January 2007 Cabinet gets a score of 65/100.

Economic reform

Here, the picture is bleak. There is no common understanding among the various parties of the reforms that are needed to bring prosperity to the people.

The ad hoc approach to infrastructure and related activities does not bode well for any kind of meaningful reforms, and in fact, contains the seeds of massive rent seeking, likely to distort the next few elections.

The non-competitive procurement and the uniform LKR 30 billion cost bruited about for the widely different Southern, airport and Kandy expressways exemplify the problem. (See Choices: Toll or Troll).

This government has not even done the minimum that a government should do, which is to not erode the forced savings of the people by keeping EPF and ETF interest rates above the inflation rate. (See The Thrift Column - Its fiscal stupid)

It is actually violating all norms of good economic governance by seeking to use those captive funds to float risky ventures such as Mihin Air. (See Choices: Airline or Airport)

The permanent-campaign mentality of the President and his close advisors suggests that the hard decisions necessary for reform are unlikely to be taken by this government.

The pattern of intrusive control of ministerial subjects by the Presidential Office, perhaps more accentuated than under previous Presidents, does not leave room for much hope that the reform minded ministers in either party will be able to push through any reforms.

Whether or not economic reform will happen depends on the rule of law. Possibly, a sustainable solution to the problem of finding a political solution acceptable to the minorities will also depend on adherence to the rule of law.

Invoking the optimal optimism humanly possible, I give a score of 10/100 on the second part of the test.

That yields a composite score of 75/200 (37.5%), which is about par for the course in this land of missed opportunities.

The glass may not be half full (See Choices: Half full or half empty?) But it is at least closer to half full than empty, which it was in the days of MMMOUs with the JVP, JHU and the UNP.

Rule of law

Sri Lanka is, at this time, not a country where the rule of law exists.

The Constitution is being blithely violated on a daily basis by the President through his marked lack of enthusiasm to get the Constitutional Council appointed as required by the 17th Amendment and by his proactive violation of the Constitution through the appointment of the IGP, the members of the Human Rights Commission and so on.

This violation of the highest law in the land has been condoned by various entities, including the Supreme Court, the Leader of the Opposition and the Speaker of Parliament.

It must be noted that the sabotaging of the 17th Amendment did not start with the present President.

But that process was taken to the next level by the making of extra-constitutional appointments during his term.

If the highest authority in the land does what he pleases, unconstrained by the supreme law, we live in a country that is ruled by a President not by law.

We should not be surprised that law is violated at all levels of the executive.

A simple example that everyone can see is the flagrant abuse of public funds by entities such as the National Lotteries Board to erect patently political hoardings to celebrate the first anniversary of the assumption of power by the President.

If there is no rule of law, the prospects of the MPs who took their oaths as ministers on January 28th are bleak indeed.

Even if they are not summarily discarded like the President's erstwhile allies, it is unlikely that they will be able to do anything meaningful with their portfolios, subject as they will be to the rule of men (namely the President, his siblings and close associates) rather than the rule of law.

So my recommendation is that all persons of goodwill, in Parliament as well as outside, should give priority to either implementing the 17th Amendment fully (including the provisions regarding the Elections Commission), or amending it to a form they can stomach and then implementing the amended Constitution faithfully.

A government that violates its own Constitution will not be trusted by decent investors and partners, let alone by the LTTE, whose agreement at the negotiating table is essential if this cancer of war is to be eliminated from the Sri Lankan body politic.

Such a government should not be trusted by its people either.

Source: News reports

Note: Party affiliations are per Supreme Court, and are subject to interpretation.

Is it good for Sri Lanka and its future? Each person will have to make up his or her mind, but here is my take, for whatever it's worth.

The test that I apply to anything political in Sri Lanka is a two-fold one: is it likely to contribute to restoring peace to this land and is it likely to contribute to economic reforms that will bring prosperity to its people?

If it passes both parts, it is good; if it passes none, it is bad; if it passes only one, it is not too bad and may be better than the norm. After all, we are in Sri Lanka, where under-performance is a finely honed art.

By this test, this political development is better than the norm.

But it is definitely better than the misbegotten, meaningless MOU between the UNP and the President that is being bemoaned by the international media and by those who should know better.

The only result of that particular MMMOU was blank-cheque approval of the budget by the opposition party and business as usual by the President.

This is a controversial position that requires some justification.

Constitution

We must begin from the 1978 Constitution, memorably described as the "bahubootha vyavastava" by the previous President.

The 1978 Constitution is a bad adaptation of the original republican, division-of-power constitution, the US Constitution that came into effect in 1789. The original stood the test of time much better than the bad copies: it has been amended only 27 times (actually even less, if one gets into the details) in its almost 218-year history.

The Sri Lankan Constitution of 1978 (and its proximate model, the French Constitution of 1958) have been amended 17 times in their much shorter histories. (Here, as with the party affiliations of the current Cabinet, ambiguity exists, but not enough to detract from the argument).

In the bastard versions, more so in Sri Lanka than in France, the real power resides in the Presidency. The legislature matters little; the parties even less. Of the judiciary, the less said the better.

Unlike in the original, the cabinet has to be selected from among sitting members of the legislature in Sri Lanka, violating the fundamental principle of separation of power between the legislature and the executive.

In the US, the President can take people from Congress to his Cabinet, but at that point they leave the legislative branch and join the executive. And he does take from the "other" party.

Bill Clinton's last secretary of defense, Bill Cohen, was a Republican Senator who resigned the Senate to serve on Cabinet; George W. Bush's secretary of transportation was Norm Mineta, a former Democratic congressman, who resigned from the House.

The absence of a fixed term for the legislature and the criminally abused power to dissolve Parliament are but two among the many reasons why the executive overwhelms the legislature in Sri Lanka.

In the early years, parties were able to maintain discipline because of prohibitions on cross-overs, etc.

However, under current Supreme-Court interpretation, there does not seem to be any way to remove an MP who violates party discipline.

This has exacerbated the sclerosis of the party system. The parties are far from democratic in their internal governance, so the apparent perversity of the Supreme Court may actually not be too wrong.

Peace

If one thing can be concluded from the sad history of this country since the breaking of the 1948 political compact with the minorities by the unilateral adoption of the 1972 Constitution, it is that, at minimum, we need a new constitutional arrangement that devolves more power to the Tamil minority living in the Northern and (parts of) the Eastern provinces than did any of the previous Constitutions.

The necessary (but not sufficient) condition to peace is, therefore, a new Constitution.

How does one get a new Constitution? Two-thirds majority in the legislature and a majority of the votes cast in a referendum, according to the 1978 Constitution.

Given the malign results of our one experience in extra-legal Constitution-making in 1972, one hopes fervently that it will not be repeated, however bahubootha the 1978 Constitution is.

Are we closer to meeting the constitutional requirement after the entry to Cabinet of the UNP reform group than on previous occasions when constitution making was or could have been attempted, such as 1998, 2000, 2003, etc.? Possibly.

Until 2000, the government did not have a complete draft of the "package" despite repeated and insistent demands for cooperation from the opposition.

They were being asked to sign on a blank sheet of paper, with the details to be filled in by the President later.

What the proposed referendum of April 1998 (cancelled when the then President got cold feet because of the Dalada bomb) was going to be on was a mystery. The package was not ready.

Much has been made of the bad behavior of UNP MPs in 2000 when the package was presented to Parliament, but neither they nor the TULF could have accepted a hurriedly cobbled together package that had many surprises, especially with regard to elections.

In 2003, the childish behavior of a faction of the UNP sabotaged any chances of winning the support of the President and her party for any constitutional reforms.

In retrospect, it appears that the strategy of then Prime Minister was to drag out the peace negotiations until the Presidential election that he thought was his to win.

The cohabitation of 2001-2004 was a classic opportunity to bring the two main parties together on a common platform to enact constitutional reforms. Both parties were weak and needed each other; the international environment was conducive and the ceasefire existed. But in early December 2003, with the collapse of the Mano-Malik negotiations, that opportunity too was squandered.

Now, in the second year of the six-year term of the President, the prospects for a 2/3rd majority are closer than ever before. And the components of a new Constitution exist in the flotsam and jetsam of previous constitutional reform efforts.

The current President has yet to demonstrate that he has the necessary understanding and commitment to provide leadership for the historic task of winning a majority of the votes cast at a referendum.

But, he is trusted by the Sinhala majority, more than his immediate predecessors as President and Prime Minister.

He passes the "who can be trusted to negotiate the fate of the Ampara district?" test with higher marks.

President Nixon, who was trusted by conservatives, was able to establish relations with China, and complete a liberal project that would have been almost impossible for a liberal President.

In the same way, the current President may be the one to convince the Sinhala majority to make peace with the minorities.

Despite himself, he may enter the history books that eluded his predecessors and win reelection for reason in 2011.

And with the concrete collaboration between the UNP and the SLFP led coalition starting with the appointment of the new Cabinet (in contrast to the MOU), it may be that this government is closer to a 2/3rd majority than any other since the fake 4/5th majority enjoyed by the Jayawardene government under the 1978 Constitution.

The fact that this gargantuan Cabinet includes pretty much all the parties except the extremist ones, and has seven minority representatives (14%) within it is also a positive factor.

Therefore, on the first part of the test, the January 2007 Cabinet gets a score of 65/100.

Economic reform

Here, the picture is bleak. There is no common understanding among the various parties of the reforms that are needed to bring prosperity to the people.

The ad hoc approach to infrastructure and related activities does not bode well for any kind of meaningful reforms, and in fact, contains the seeds of massive rent seeking, likely to distort the next few elections.

The non-competitive procurement and the uniform LKR 30 billion cost bruited about for the widely different Southern, airport and Kandy expressways exemplify the problem. (See Choices: Toll or Troll).

This government has not even done the minimum that a government should do, which is to not erode the forced savings of the people by keeping EPF and ETF interest rates above the inflation rate. (See The Thrift Column - Its fiscal stupid)

It is actually violating all norms of good economic governance by seeking to use those captive funds to float risky ventures such as Mihin Air. (See Choices: Airline or Airport)

The permanent-campaign mentality of the President and his close advisors suggests that the hard decisions necessary for reform are unlikely to be taken by this government.

The pattern of intrusive control of ministerial subjects by the Presidential Office, perhaps more accentuated than under previous Presidents, does not leave room for much hope that the reform minded ministers in either party will be able to push through any reforms.

Whether or not economic reform will happen depends on the rule of law. Possibly, a sustainable solution to the problem of finding a political solution acceptable to the minorities will also depend on adherence to the rule of law.

Invoking the optimal optimism humanly possible, I give a score of 10/100 on the second part of the test.

That yields a composite score of 75/200 (37.5%), which is about par for the course in this land of missed opportunities.

The glass may not be half full (See Choices: Half full or half empty?) But it is at least closer to half full than empty, which it was in the days of MMMOUs with the JVP, JHU and the UNP.

Rule of law

Sri Lanka is, at this time, not a country where the rule of law exists.

The Constitution is being blithely violated on a daily basis by the President through his marked lack of enthusiasm to get the Constitutional Council appointed as required by the 17th Amendment and by his proactive violation of the Constitution through the appointment of the IGP, the members of the Human Rights Commission and so on.

This violation of the highest law in the land has been condoned by various entities, including the Supreme Court, the Leader of the Opposition and the Speaker of Parliament.

It must be noted that the sabotaging of the 17th Amendment did not start with the present President.

But that process was taken to the next level by the making of extra-constitutional appointments during his term.

If the highest authority in the land does what he pleases, unconstrained by the supreme law, we live in a country that is ruled by a President not by law.

We should not be surprised that law is violated at all levels of the executive.

A simple example that everyone can see is the flagrant abuse of public funds by entities such as the National Lotteries Board to erect patently political hoardings to celebrate the first anniversary of the assumption of power by the President.

If there is no rule of law, the prospects of the MPs who took their oaths as ministers on January 28th are bleak indeed.

Even if they are not summarily discarded like the President's erstwhile allies, it is unlikely that they will be able to do anything meaningful with their portfolios, subject as they will be to the rule of men (namely the President, his siblings and close associates) rather than the rule of law.

So my recommendation is that all persons of goodwill, in Parliament as well as outside, should give priority to either implementing the 17th Amendment fully (including the provisions regarding the Elections Commission), or amending it to a form they can stomach and then implementing the amended Constitution faithfully.

A government that violates its own Constitution will not be trusted by decent investors and partners, let alone by the LTTE, whose agreement at the negotiating table is essential if this cancer of war is to be eliminated from the Sri Lankan body politic.

Such a government should not be trusted by its people either. Choices: Rule of law or rule of men?

January 29, 2007 (LBO) -- What shall we make of the new 52-member, multi-party Cabinet (depicted in Figure 1) sworn in on January 28th, 2007?

Source: News reports

Note: Party affiliations are per Supreme Court, and are subject to interpretation.

Is it good for Sri Lanka and its future? Each person will have to make up his or her mind, but here is my take, for whatever it's worth.

The test that I apply to anything political in Sri Lanka is a two-fold one: is it likely to contribute to restoring peace to this land and is it likely to contribute to economic reforms that will bring prosperity to its people?

If it passes both parts, it is good; if it passes none, it is bad; if it passes only one, it is not too bad and may be better than the norm. After all, we are in Sri Lanka, where under-performance is a finely honed art.

By this test, this political development is better than the norm.

But it is definitely better than the misbegotten, meaningless MOU between the UNP and the President that is being bemoaned by the international media and by those who should know better.

The only result of that particular MMMOU was blank-cheque approval of the budget by the opposition party and business as usual by the President.

This is a controversial position that requires some justification.

Constitution

We must begin from the 1978 Constitution, memorably described as the "bahubootha vyavastava" by the previous President.

The 1978 Constitution is a bad adaptation of the original republican, division-of-power constitution, the US Constitution that came into effect in 1789. The original stood the test of time much better than the bad copies: it has been amended only 27 times (actually even less, if one gets into the details) in its almost 218-year history.

The Sri Lankan Constitution of 1978 (and its proximate model, the French Constitution of 1958) have been amended 17 times in their much shorter histories. (Here, as with the party affiliations of the current Cabinet, ambiguity exists, but not enough to detract from the argument).

In the bastard versions, more so in Sri Lanka than in France, the real power resides in the Presidency. The legislature matters little; the parties even less. Of the judiciary, the less said the better.

Unlike in the original, the cabinet has to be selected from among sitting members of the legislature in Sri Lanka, violating the fundamental principle of separation of power between the legislature and the executive.

In the US, the President can take people from Congress to his Cabinet, but at that point they leave the legislative branch and join the executive. And he does take from the "other" party.

Bill Clinton's last secretary of defense, Bill Cohen, was a Republican Senator who resigned the Senate to serve on Cabinet; George W. Bush's secretary of transportation was Norm Mineta, a former Democratic congressman, who resigned from the House.

The absence of a fixed term for the legislature and the criminally abused power to dissolve Parliament are but two among the many reasons why the executive overwhelms the legislature in Sri Lanka.

In the early years, parties were able to maintain discipline because of prohibitions on cross-overs, etc.

However, under current Supreme-Court interpretation, there does not seem to be any way to remove an MP who violates party discipline.

This has exacerbated the sclerosis of the party system. The parties are far from democratic in their internal governance, so the apparent perversity of the Supreme Court may actually not be too wrong.

Peace

If one thing can be concluded from the sad history of this country since the breaking of the 1948 political compact with the minorities by the unilateral adoption of the 1972 Constitution, it is that, at minimum, we need a new constitutional arrangement that devolves more power to the Tamil minority living in the Northern and (parts of) the Eastern provinces than did any of the previous Constitutions.

The necessary (but not sufficient) condition to peace is, therefore, a new Constitution.

How does one get a new Constitution? Two-thirds majority in the legislature and a majority of the votes cast in a referendum, according to the 1978 Constitution.

Given the malign results of our one experience in extra-legal Constitution-making in 1972, one hopes fervently that it will not be repeated, however bahubootha the 1978 Constitution is.

Are we closer to meeting the constitutional requirement after the entry to Cabinet of the UNP reform group than on previous occasions when constitution making was or could have been attempted, such as 1998, 2000, 2003, etc.? Possibly.

Until 2000, the government did not have a complete draft of the "package" despite repeated and insistent demands for cooperation from the opposition.

They were being asked to sign on a blank sheet of paper, with the details to be filled in by the President later.

What the proposed referendum of April 1998 (cancelled when the then President got cold feet because of the Dalada bomb) was going to be on was a mystery. The package was not ready.

Much has been made of the bad behavior of UNP MPs in 2000 when the package was presented to Parliament, but neither they nor the TULF could have accepted a hurriedly cobbled together package that had many surprises, especially with regard to elections.

In 2003, the childish behavior of a faction of the UNP sabotaged any chances of winning the support of the President and her party for any constitutional reforms.

In retrospect, it appears that the strategy of then Prime Minister was to drag out the peace negotiations until the Presidential election that he thought was his to win.

The cohabitation of 2001-2004 was a classic opportunity to bring the two main parties together on a common platform to enact constitutional reforms. Both parties were weak and needed each other; the international environment was conducive and the ceasefire existed. But in early December 2003, with the collapse of the Mano-Malik negotiations, that opportunity too was squandered.

Now, in the second year of the six-year term of the President, the prospects for a 2/3rd majority are closer than ever before. And the components of a new Constitution exist in the flotsam and jetsam of previous constitutional reform efforts.

The current President has yet to demonstrate that he has the necessary understanding and commitment to provide leadership for the historic task of winning a majority of the votes cast at a referendum.

But, he is trusted by the Sinhala majority, more than his immediate predecessors as President and Prime Minister.

He passes the "who can be trusted to negotiate the fate of the Ampara district?" test with higher marks.

President Nixon, who was trusted by conservatives, was able to establish relations with China, and complete a liberal project that would have been almost impossible for a liberal President.

In the same way, the current President may be the one to convince the Sinhala majority to make peace with the minorities.

Despite himself, he may enter the history books that eluded his predecessors and win reelection for reason in 2011.

And with the concrete collaboration between the UNP and the SLFP led coalition starting with the appointment of the new Cabinet (in contrast to the MOU), it may be that this government is closer to a 2/3rd majority than any other since the fake 4/5th majority enjoyed by the Jayawardene government under the 1978 Constitution.

The fact that this gargantuan Cabinet includes pretty much all the parties except the extremist ones, and has seven minority representatives (14%) within it is also a positive factor.

Therefore, on the first part of the test, the January 2007 Cabinet gets a score of 65/100.

Economic reform

Here, the picture is bleak. There is no common understanding among the various parties of the reforms that are needed to bring prosperity to the people.

The ad hoc approach to infrastructure and related activities does not bode well for any kind of meaningful reforms, and in fact, contains the seeds of massive rent seeking, likely to distort the next few elections.

The non-competitive procurement and the uniform LKR 30 billion cost bruited about for the widely different Southern, airport and Kandy expressways exemplify the problem. (See Choices: Toll or Troll).

This government has not even done the minimum that a government should do, which is to not erode the forced savings of the people by keeping EPF and ETF interest rates above the inflation rate. (See The Thrift Column - Its fiscal stupid)

It is actually violating all norms of good economic governance by seeking to use those captive funds to float risky ventures such as Mihin Air. (See Choices: Airline or Airport)

The permanent-campaign mentality of the President and his close advisors suggests that the hard decisions necessary for reform are unlikely to be taken by this government.

The pattern of intrusive control of ministerial subjects by the Presidential Office, perhaps more accentuated than under previous Presidents, does not leave room for much hope that the reform minded ministers in either party will be able to push through any reforms.

Whether or not economic reform will happen depends on the rule of law. Possibly, a sustainable solution to the problem of finding a political solution acceptable to the minorities will also depend on adherence to the rule of law.

Invoking the optimal optimism humanly possible, I give a score of 10/100 on the second part of the test.

That yields a composite score of 75/200 (37.5%), which is about par for the course in this land of missed opportunities.

The glass may not be half full (See Choices: Half full or half empty?) But it is at least closer to half full than empty, which it was in the days of MMMOUs with the JVP, JHU and the UNP.

Rule of law

Sri Lanka is, at this time, not a country where the rule of law exists.

The Constitution is being blithely violated on a daily basis by the President through his marked lack of enthusiasm to get the Constitutional Council appointed as required by the 17th Amendment and by his proactive violation of the Constitution through the appointment of the IGP, the members of the Human Rights Commission and so on.

This violation of the highest law in the land has been condoned by various entities, including the Supreme Court, the Leader of the Opposition and the Speaker of Parliament.

It must be noted that the sabotaging of the 17th Amendment did not start with the present President.

But that process was taken to the next level by the making of extra-constitutional appointments during his term.

If the highest authority in the land does what he pleases, unconstrained by the supreme law, we live in a country that is ruled by a President not by law.

We should not be surprised that law is violated at all levels of the executive.

A simple example that everyone can see is the flagrant abuse of public funds by entities such as the National Lotteries Board to erect patently political hoardings to celebrate the first anniversary of the assumption of power by the President.

If there is no rule of law, the prospects of the MPs who took their oaths as ministers on January 28th are bleak indeed.

Even if they are not summarily discarded like the President's erstwhile allies, it is unlikely that they will be able to do anything meaningful with their portfolios, subject as they will be to the rule of men (namely the President, his siblings and close associates) rather than the rule of law.

So my recommendation is that all persons of goodwill, in Parliament as well as outside, should give priority to either implementing the 17th Amendment fully (including the provisions regarding the Elections Commission), or amending it to a form they can stomach and then implementing the amended Constitution faithfully.

A government that violates its own Constitution will not be trusted by decent investors and partners, let alone by the LTTE, whose agreement at the negotiating table is essential if this cancer of war is to be eliminated from the Sri Lankan body politic.

Such a government should not be trusted by its people either.

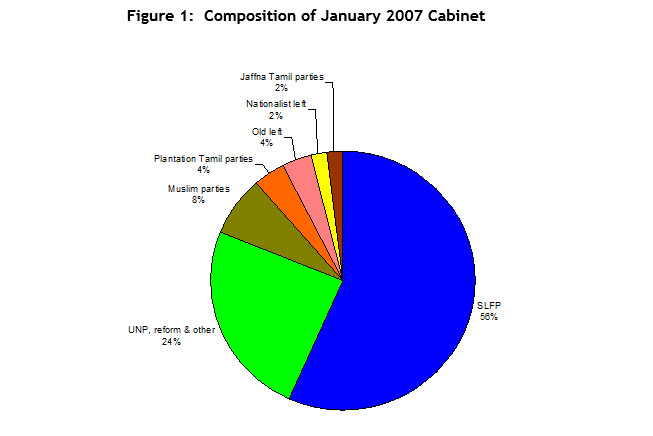

Source: News reports

Note: Party affiliations are per Supreme Court, and are subject to interpretation.

Is it good for Sri Lanka and its future? Each person will have to make up his or her mind, but here is my take, for whatever it's worth.

The test that I apply to anything political in Sri Lanka is a two-fold one: is it likely to contribute to restoring peace to this land and is it likely to contribute to economic reforms that will bring prosperity to its people?

If it passes both parts, it is good; if it passes none, it is bad; if it passes only one, it is not too bad and may be better than the norm. After all, we are in Sri Lanka, where under-performance is a finely honed art.

By this test, this political development is better than the norm.

But it is definitely better than the misbegotten, meaningless MOU between the UNP and the President that is being bemoaned by the international media and by those who should know better.

The only result of that particular MMMOU was blank-cheque approval of the budget by the opposition party and business as usual by the President.

This is a controversial position that requires some justification.

Constitution

We must begin from the 1978 Constitution, memorably described as the "bahubootha vyavastava" by the previous President.

The 1978 Constitution is a bad adaptation of the original republican, division-of-power constitution, the US Constitution that came into effect in 1789. The original stood the test of time much better than the bad copies: it has been amended only 27 times (actually even less, if one gets into the details) in its almost 218-year history.

The Sri Lankan Constitution of 1978 (and its proximate model, the French Constitution of 1958) have been amended 17 times in their much shorter histories. (Here, as with the party affiliations of the current Cabinet, ambiguity exists, but not enough to detract from the argument).

In the bastard versions, more so in Sri Lanka than in France, the real power resides in the Presidency. The legislature matters little; the parties even less. Of the judiciary, the less said the better.

Unlike in the original, the cabinet has to be selected from among sitting members of the legislature in Sri Lanka, violating the fundamental principle of separation of power between the legislature and the executive.

In the US, the President can take people from Congress to his Cabinet, but at that point they leave the legislative branch and join the executive. And he does take from the "other" party.

Bill Clinton's last secretary of defense, Bill Cohen, was a Republican Senator who resigned the Senate to serve on Cabinet; George W. Bush's secretary of transportation was Norm Mineta, a former Democratic congressman, who resigned from the House.

The absence of a fixed term for the legislature and the criminally abused power to dissolve Parliament are but two among the many reasons why the executive overwhelms the legislature in Sri Lanka.

In the early years, parties were able to maintain discipline because of prohibitions on cross-overs, etc.

However, under current Supreme-Court interpretation, there does not seem to be any way to remove an MP who violates party discipline.

This has exacerbated the sclerosis of the party system. The parties are far from democratic in their internal governance, so the apparent perversity of the Supreme Court may actually not be too wrong.

Peace

If one thing can be concluded from the sad history of this country since the breaking of the 1948 political compact with the minorities by the unilateral adoption of the 1972 Constitution, it is that, at minimum, we need a new constitutional arrangement that devolves more power to the Tamil minority living in the Northern and (parts of) the Eastern provinces than did any of the previous Constitutions.

The necessary (but not sufficient) condition to peace is, therefore, a new Constitution.

How does one get a new Constitution? Two-thirds majority in the legislature and a majority of the votes cast in a referendum, according to the 1978 Constitution.

Given the malign results of our one experience in extra-legal Constitution-making in 1972, one hopes fervently that it will not be repeated, however bahubootha the 1978 Constitution is.

Are we closer to meeting the constitutional requirement after the entry to Cabinet of the UNP reform group than on previous occasions when constitution making was or could have been attempted, such as 1998, 2000, 2003, etc.? Possibly.

Until 2000, the government did not have a complete draft of the "package" despite repeated and insistent demands for cooperation from the opposition.

They were being asked to sign on a blank sheet of paper, with the details to be filled in by the President later.

What the proposed referendum of April 1998 (cancelled when the then President got cold feet because of the Dalada bomb) was going to be on was a mystery. The package was not ready.

Much has been made of the bad behavior of UNP MPs in 2000 when the package was presented to Parliament, but neither they nor the TULF could have accepted a hurriedly cobbled together package that had many surprises, especially with regard to elections.

In 2003, the childish behavior of a faction of the UNP sabotaged any chances of winning the support of the President and her party for any constitutional reforms.

In retrospect, it appears that the strategy of then Prime Minister was to drag out the peace negotiations until the Presidential election that he thought was his to win.

The cohabitation of 2001-2004 was a classic opportunity to bring the two main parties together on a common platform to enact constitutional reforms. Both parties were weak and needed each other; the international environment was conducive and the ceasefire existed. But in early December 2003, with the collapse of the Mano-Malik negotiations, that opportunity too was squandered.

Now, in the second year of the six-year term of the President, the prospects for a 2/3rd majority are closer than ever before. And the components of a new Constitution exist in the flotsam and jetsam of previous constitutional reform efforts.

The current President has yet to demonstrate that he has the necessary understanding and commitment to provide leadership for the historic task of winning a majority of the votes cast at a referendum.

But, he is trusted by the Sinhala majority, more than his immediate predecessors as President and Prime Minister.

He passes the "who can be trusted to negotiate the fate of the Ampara district?" test with higher marks.

President Nixon, who was trusted by conservatives, was able to establish relations with China, and complete a liberal project that would have been almost impossible for a liberal President.

In the same way, the current President may be the one to convince the Sinhala majority to make peace with the minorities.

Despite himself, he may enter the history books that eluded his predecessors and win reelection for reason in 2011.

And with the concrete collaboration between the UNP and the SLFP led coalition starting with the appointment of the new Cabinet (in contrast to the MOU), it may be that this government is closer to a 2/3rd majority than any other since the fake 4/5th majority enjoyed by the Jayawardene government under the 1978 Constitution.

The fact that this gargantuan Cabinet includes pretty much all the parties except the extremist ones, and has seven minority representatives (14%) within it is also a positive factor.

Therefore, on the first part of the test, the January 2007 Cabinet gets a score of 65/100.

Economic reform

Here, the picture is bleak. There is no common understanding among the various parties of the reforms that are needed to bring prosperity to the people.

The ad hoc approach to infrastructure and related activities does not bode well for any kind of meaningful reforms, and in fact, contains the seeds of massive rent seeking, likely to distort the next few elections.

The non-competitive procurement and the uniform LKR 30 billion cost bruited about for the widely different Southern, airport and Kandy expressways exemplify the problem. (See Choices: Toll or Troll).

This government has not even done the minimum that a government should do, which is to not erode the forced savings of the people by keeping EPF and ETF interest rates above the inflation rate. (See The Thrift Column - Its fiscal stupid)

It is actually violating all norms of good economic governance by seeking to use those captive funds to float risky ventures such as Mihin Air. (See Choices: Airline or Airport)

The permanent-campaign mentality of the President and his close advisors suggests that the hard decisions necessary for reform are unlikely to be taken by this government.

The pattern of intrusive control of ministerial subjects by the Presidential Office, perhaps more accentuated than under previous Presidents, does not leave room for much hope that the reform minded ministers in either party will be able to push through any reforms.

Whether or not economic reform will happen depends on the rule of law. Possibly, a sustainable solution to the problem of finding a political solution acceptable to the minorities will also depend on adherence to the rule of law.

Invoking the optimal optimism humanly possible, I give a score of 10/100 on the second part of the test.

That yields a composite score of 75/200 (37.5%), which is about par for the course in this land of missed opportunities.

The glass may not be half full (See Choices: Half full or half empty?) But it is at least closer to half full than empty, which it was in the days of MMMOUs with the JVP, JHU and the UNP.

Rule of law

Sri Lanka is, at this time, not a country where the rule of law exists.

The Constitution is being blithely violated on a daily basis by the President through his marked lack of enthusiasm to get the Constitutional Council appointed as required by the 17th Amendment and by his proactive violation of the Constitution through the appointment of the IGP, the members of the Human Rights Commission and so on.

This violation of the highest law in the land has been condoned by various entities, including the Supreme Court, the Leader of the Opposition and the Speaker of Parliament.

It must be noted that the sabotaging of the 17th Amendment did not start with the present President.

But that process was taken to the next level by the making of extra-constitutional appointments during his term.

If the highest authority in the land does what he pleases, unconstrained by the supreme law, we live in a country that is ruled by a President not by law.

We should not be surprised that law is violated at all levels of the executive.

A simple example that everyone can see is the flagrant abuse of public funds by entities such as the National Lotteries Board to erect patently political hoardings to celebrate the first anniversary of the assumption of power by the President.

If there is no rule of law, the prospects of the MPs who took their oaths as ministers on January 28th are bleak indeed.

Even if they are not summarily discarded like the President's erstwhile allies, it is unlikely that they will be able to do anything meaningful with their portfolios, subject as they will be to the rule of men (namely the President, his siblings and close associates) rather than the rule of law.

So my recommendation is that all persons of goodwill, in Parliament as well as outside, should give priority to either implementing the 17th Amendment fully (including the provisions regarding the Elections Commission), or amending it to a form they can stomach and then implementing the amended Constitution faithfully.

A government that violates its own Constitution will not be trusted by decent investors and partners, let alone by the LTTE, whose agreement at the negotiating table is essential if this cancer of war is to be eliminated from the Sri Lankan body politic.

Such a government should not be trusted by its people either.

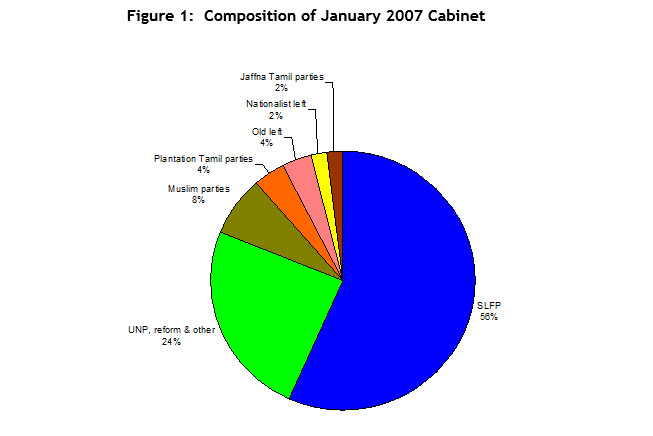

Source: News reports

Note: Party affiliations are per Supreme Court, and are subject to interpretation.

Is it good for Sri Lanka and its future? Each person will have to make up his or her mind, but here is my take, for whatever it's worth.

The test that I apply to anything political in Sri Lanka is a two-fold one: is it likely to contribute to restoring peace to this land and is it likely to contribute to economic reforms that will bring prosperity to its people?

If it passes both parts, it is good; if it passes none, it is bad; if it passes only one, it is not too bad and may be better than the norm. After all, we are in Sri Lanka, where under-performance is a finely honed art.

By this test, this political development is better than the norm.

But it is definitely better than the misbegotten, meaningless MOU between the UNP and the President that is being bemoaned by the international media and by those who should know better.

The only result of that particular MMMOU was blank-cheque approval of the budget by the opposition party and business as usual by the President.

This is a controversial position that requires some justification.

Constitution

We must begin from the 1978 Constitution, memorably described as the "bahubootha vyavastava" by the previous President.

The 1978 Constitution is a bad adaptation of the original republican, division-of-power constitution, the US Constitution that came into effect in 1789. The original stood the test of time much better than the bad copies: it has been amended only 27 times (actually even less, if one gets into the details) in its almost 218-year history.

The Sri Lankan Constitution of 1978 (and its proximate model, the French Constitution of 1958) have been amended 17 times in their much shorter histories. (Here, as with the party affiliations of the current Cabinet, ambiguity exists, but not enough to detract from the argument).

In the bastard versions, more so in Sri Lanka than in France, the real power resides in the Presidency. The legislature matters little; the parties even less. Of the judiciary, the less said the better.

Unlike in the original, the cabinet has to be selected from among sitting members of the legislature in Sri Lanka, violating the fundamental principle of separation of power between the legislature and the executive.

In the US, the President can take people from Congress to his Cabinet, but at that point they leave the legislative branch and join the executive. And he does take from the "other" party.

Bill Clinton's last secretary of defense, Bill Cohen, was a Republican Senator who resigned the Senate to serve on Cabinet; George W. Bush's secretary of transportation was Norm Mineta, a former Democratic congressman, who resigned from the House.

The absence of a fixed term for the legislature and the criminally abused power to dissolve Parliament are but two among the many reasons why the executive overwhelms the legislature in Sri Lanka.

In the early years, parties were able to maintain discipline because of prohibitions on cross-overs, etc.

However, under current Supreme-Court interpretation, there does not seem to be any way to remove an MP who violates party discipline.

This has exacerbated the sclerosis of the party system. The parties are far from democratic in their internal governance, so the apparent perversity of the Supreme Court may actually not be too wrong.

Peace

If one thing can be concluded from the sad history of this country since the breaking of the 1948 political compact with the minorities by the unilateral adoption of the 1972 Constitution, it is that, at minimum, we need a new constitutional arrangement that devolves more power to the Tamil minority living in the Northern and (parts of) the Eastern provinces than did any of the previous Constitutions.

The necessary (but not sufficient) condition to peace is, therefore, a new Constitution.

How does one get a new Constitution? Two-thirds majority in the legislature and a majority of the votes cast in a referendum, according to the 1978 Constitution.

Given the malign results of our one experience in extra-legal Constitution-making in 1972, one hopes fervently that it will not be repeated, however bahubootha the 1978 Constitution is.

Are we closer to meeting the constitutional requirement after the entry to Cabinet of the UNP reform group than on previous occasions when constitution making was or could have been attempted, such as 1998, 2000, 2003, etc.? Possibly.

Until 2000, the government did not have a complete draft of the "package" despite repeated and insistent demands for cooperation from the opposition.

They were being asked to sign on a blank sheet of paper, with the details to be filled in by the President later.

What the proposed referendum of April 1998 (cancelled when the then President got cold feet because of the Dalada bomb) was going to be on was a mystery. The package was not ready.

Much has been made of the bad behavior of UNP MPs in 2000 when the package was presented to Parliament, but neither they nor the TULF could have accepted a hurriedly cobbled together package that had many surprises, especially with regard to elections.

In 2003, the childish behavior of a faction of the UNP sabotaged any chances of winning the support of the President and her party for any constitutional reforms.

In retrospect, it appears that the strategy of then Prime Minister was to drag out the peace negotiations until the Presidential election that he thought was his to win.

The cohabitation of 2001-2004 was a classic opportunity to bring the two main parties together on a common platform to enact constitutional reforms. Both parties were weak and needed each other; the international environment was conducive and the ceasefire existed. But in early December 2003, with the collapse of the Mano-Malik negotiations, that opportunity too was squandered.

Now, in the second year of the six-year term of the President, the prospects for a 2/3rd majority are closer than ever before. And the components of a new Constitution exist in the flotsam and jetsam of previous constitutional reform efforts.

The current President has yet to demonstrate that he has the necessary understanding and commitment to provide leadership for the historic task of winning a majority of the votes cast at a referendum.

But, he is trusted by the Sinhala majority, more than his immediate predecessors as President and Prime Minister.

He passes the "who can be trusted to negotiate the fate of the Ampara district?" test with higher marks.

President Nixon, who was trusted by conservatives, was able to establish relations with China, and complete a liberal project that would have been almost impossible for a liberal President.

In the same way, the current President may be the one to convince the Sinhala majority to make peace with the minorities.

Despite himself, he may enter the history books that eluded his predecessors and win reelection for reason in 2011.

And with the concrete collaboration between the UNP and the SLFP led coalition starting with the appointment of the new Cabinet (in contrast to the MOU), it may be that this government is closer to a 2/3rd majority than any other since the fake 4/5th majority enjoyed by the Jayawardene government under the 1978 Constitution.

The fact that this gargantuan Cabinet includes pretty much all the parties except the extremist ones, and has seven minority representatives (14%) within it is also a positive factor.

Therefore, on the first part of the test, the January 2007 Cabinet gets a score of 65/100.

Economic reform

Here, the picture is bleak. There is no common understanding among the various parties of the reforms that are needed to bring prosperity to the people.

The ad hoc approach to infrastructure and related activities does not bode well for any kind of meaningful reforms, and in fact, contains the seeds of massive rent seeking, likely to distort the next few elections.

The non-competitive procurement and the uniform LKR 30 billion cost bruited about for the widely different Southern, airport and Kandy expressways exemplify the problem. (See Choices: Toll or Troll).

This government has not even done the minimum that a government should do, which is to not erode the forced savings of the people by keeping EPF and ETF interest rates above the inflation rate. (See The Thrift Column - Its fiscal stupid)

It is actually violating all norms of good economic governance by seeking to use those captive funds to float risky ventures such as Mihin Air. (See Choices: Airline or Airport)

The permanent-campaign mentality of the President and his close advisors suggests that the hard decisions necessary for reform are unlikely to be taken by this government.

The pattern of intrusive control of ministerial subjects by the Presidential Office, perhaps more accentuated than under previous Presidents, does not leave room for much hope that the reform minded ministers in either party will be able to push through any reforms.

Whether or not economic reform will happen depends on the rule of law. Possibly, a sustainable solution to the problem of finding a political solution acceptable to the minorities will also depend on adherence to the rule of law.

Invoking the optimal optimism humanly possible, I give a score of 10/100 on the second part of the test.

That yields a composite score of 75/200 (37.5%), which is about par for the course in this land of missed opportunities.

The glass may not be half full (See Choices: Half full or half empty?) But it is at least closer to half full than empty, which it was in the days of MMMOUs with the JVP, JHU and the UNP.

Rule of law

Sri Lanka is, at this time, not a country where the rule of law exists.

The Constitution is being blithely violated on a daily basis by the President through his marked lack of enthusiasm to get the Constitutional Council appointed as required by the 17th Amendment and by his proactive violation of the Constitution through the appointment of the IGP, the members of the Human Rights Commission and so on.

This violation of the highest law in the land has been condoned by various entities, including the Supreme Court, the Leader of the Opposition and the Speaker of Parliament.

It must be noted that the sabotaging of the 17th Amendment did not start with the present President.

But that process was taken to the next level by the making of extra-constitutional appointments during his term.

If the highest authority in the land does what he pleases, unconstrained by the supreme law, we live in a country that is ruled by a President not by law.

We should not be surprised that law is violated at all levels of the executive.

A simple example that everyone can see is the flagrant abuse of public funds by entities such as the National Lotteries Board to erect patently political hoardings to celebrate the first anniversary of the assumption of power by the President.

If there is no rule of law, the prospects of the MPs who took their oaths as ministers on January 28th are bleak indeed.

Even if they are not summarily discarded like the President's erstwhile allies, it is unlikely that they will be able to do anything meaningful with their portfolios, subject as they will be to the rule of men (namely the President, his siblings and close associates) rather than the rule of law.

So my recommendation is that all persons of goodwill, in Parliament as well as outside, should give priority to either implementing the 17th Amendment fully (including the provisions regarding the Elections Commission), or amending it to a form they can stomach and then implementing the amended Constitution faithfully.

A government that violates its own Constitution will not be trusted by decent investors and partners, let alone by the LTTE, whose agreement at the negotiating table is essential if this cancer of war is to be eliminated from the Sri Lankan body politic.

Such a government should not be trusted by its people either.

Source: News reports

Note: Party affiliations are per Supreme Court, and are subject to interpretation.

Is it good for Sri Lanka and its future? Each person will have to make up his or her mind, but here is my take, for whatever it's worth.

The test that I apply to anything political in Sri Lanka is a two-fold one: is it likely to contribute to restoring peace to this land and is it likely to contribute to economic reforms that will bring prosperity to its people?

If it passes both parts, it is good; if it passes none, it is bad; if it passes only one, it is not too bad and may be better than the norm. After all, we are in Sri Lanka, where under-performance is a finely honed art.

By this test, this political development is better than the norm.

But it is definitely better than the misbegotten, meaningless MOU between the UNP and the President that is being bemoaned by the international media and by those who should know better.

The only result of that particular MMMOU was blank-cheque approval of the budget by the opposition party and business as usual by the President.

This is a controversial position that requires some justification.

Constitution

We must begin from the 1978 Constitution, memorably described as the "bahubootha vyavastava" by the previous President.

The 1978 Constitution is a bad adaptation of the original republican, division-of-power constitution, the US Constitution that came into effect in 1789. The original stood the test of time much better than the bad copies: it has been amended only 27 times (actually even less, if one gets into the details) in its almost 218-year history.

The Sri Lankan Constitution of 1978 (and its proximate model, the French Constitution of 1958) have been amended 17 times in their much shorter histories. (Here, as with the party affiliations of the current Cabinet, ambiguity exists, but not enough to detract from the argument).

In the bastard versions, more so in Sri Lanka than in France, the real power resides in the Presidency. The legislature matters little; the parties even less. Of the judiciary, the less said the better.

Unlike in the original, the cabinet has to be selected from among sitting members of the legislature in Sri Lanka, violating the fundamental principle of separation of power between the legislature and the executive.

In the US, the President can take people from Congress to his Cabinet, but at that point they leave the legislative branch and join the executive. And he does take from the "other" party.

Bill Clinton's last secretary of defense, Bill Cohen, was a Republican Senator who resigned the Senate to serve on Cabinet; George W. Bush's secretary of transportation was Norm Mineta, a former Democratic congressman, who resigned from the House.

The absence of a fixed term for the legislature and the criminally abused power to dissolve Parliament are but two among the many reasons why the executive overwhelms the legislature in Sri Lanka.

In the early years, parties were able to maintain discipline because of prohibitions on cross-overs, etc.

However, under current Supreme-Court interpretation, there does not seem to be any way to remove an MP who violates party discipline.

This has exacerbated the sclerosis of the party system. The parties are far from democratic in their internal governance, so the apparent perversity of the Supreme Court may actually not be too wrong.

Peace

If one thing can be concluded from the sad history of this country since the breaking of the 1948 political compact with the minorities by the unilateral adoption of the 1972 Constitution, it is that, at minimum, we need a new constitutional arrangement that devolves more power to the Tamil minority living in the Northern and (parts of) the Eastern provinces than did any of the previous Constitutions.

The necessary (but not sufficient) condition to peace is, therefore, a new Constitution.

How does one get a new Constitution? Two-thirds majority in the legislature and a majority of the votes cast in a referendum, according to the 1978 Constitution.

Given the malign results of our one experience in extra-legal Constitution-making in 1972, one hopes fervently that it will not be repeated, however bahubootha the 1978 Constitution is.

Are we closer to meeting the constitutional requirement after the entry to Cabinet of the UNP reform group than on previous occasions when constitution making was or could have been attempted, such as 1998, 2000, 2003, etc.? Possibly.

Until 2000, the government did not have a complete draft of the "package" despite repeated and insistent demands for cooperation from the opposition.

They were being asked to sign on a blank sheet of paper, with the details to be filled in by the President later.

What the proposed referendum of April 1998 (cancelled when the then President got cold feet because of the Dalada bomb) was going to be on was a mystery. The package was not ready.

Much has been made of the bad behavior of UNP MPs in 2000 when the package was presented to Parliament, but neither they nor the TULF could have accepted a hurriedly cobbled together package that had many surprises, especially with regard to elections.

In 2003, the childish behavior of a faction of the UNP sabotaged any chances of winning the support of the President and her party for any constitutional reforms.

In retrospect, it appears that the strategy of then Prime Minister was to drag out the peace negotiations until the Presidential election that he thought was his to win.

The cohabitation of 2001-2004 was a classic opportunity to bring the two main parties together on a common platform to enact constitutional reforms. Both parties were weak and needed each other; the international environment was conducive and the ceasefire existed. But in early December 2003, with the collapse of the Mano-Malik negotiations, that opportunity too was squandered.

Now, in the second year of the six-year term of the President, the prospects for a 2/3rd majority are closer than ever before. And the components of a new Constitution exist in the flotsam and jetsam of previous constitutional reform efforts.

The current President has yet to demonstrate that he has the necessary understanding and commitment to provide leadership for the historic task of winning a majority of the votes cast at a referendum.

But, he is trusted by the Sinhala majority, more than his immediate predecessors as President and Prime Minister.

He passes the "who can be trusted to negotiate the fate of the Ampara district?" test with higher marks.

President Nixon, who was trusted by conservatives, was able to establish relations with China, and complete a liberal project that would have been almost impossible for a liberal President.

In the same way, the current President may be the one to convince the Sinhala majority to make peace with the minorities.

Despite himself, he may enter the history books that eluded his predecessors and win reelection for reason in 2011.

And with the concrete collaboration between the UNP and the SLFP led coalition starting with the appointment of the new Cabinet (in contrast to the MOU), it may be that this government is closer to a 2/3rd majority than any other since the fake 4/5th majority enjoyed by the Jayawardene government under the 1978 Constitution.

The fact that this gargantuan Cabinet includes pretty much all the parties except the extremist ones, and has seven minority representatives (14%) within it is also a positive factor.

Therefore, on the first part of the test, the January 2007 Cabinet gets a score of 65/100.

Economic reform

Here, the picture is bleak. There is no common understanding among the various parties of the reforms that are needed to bring prosperity to the people.

The ad hoc approach to infrastructure and related activities does not bode well for any kind of meaningful reforms, and in fact, contains the seeds of massive rent seeking, likely to distort the next few elections.

The non-competitive procurement and the uniform LKR 30 billion cost bruited about for the widely different Southern, airport and Kandy expressways exemplify the problem. (See Choices: Toll or Troll).

This government has not even done the minimum that a government should do, which is to not erode the forced savings of the people by keeping EPF and ETF interest rates above the inflation rate. (See The Thrift Column - Its fiscal stupid)

It is actually violating all norms of good economic governance by seeking to use those captive funds to float risky ventures such as Mihin Air. (See Choices: Airline or Airport)

The permanent-campaign mentality of the President and his close advisors suggests that the hard decisions necessary for reform are unlikely to be taken by this government.

The pattern of intrusive control of ministerial subjects by the Presidential Office, perhaps more accentuated than under previous Presidents, does not leave room for much hope that the reform minded ministers in either party will be able to push through any reforms.

Whether or not economic reform will happen depends on the rule of law. Possibly, a sustainable solution to the problem of finding a political solution acceptable to the minorities will also depend on adherence to the rule of law.

Invoking the optimal optimism humanly possible, I give a score of 10/100 on the second part of the test.

That yields a composite score of 75/200 (37.5%), which is about par for the course in this land of missed opportunities.

The glass may not be half full (See Choices: Half full or half empty?) But it is at least closer to half full than empty, which it was in the days of MMMOUs with the JVP, JHU and the UNP.

Rule of law

Sri Lanka is, at this time, not a country where the rule of law exists.

The Constitution is being blithely violated on a daily basis by the President through his marked lack of enthusiasm to get the Constitutional Council appointed as required by the 17th Amendment and by his proactive violation of the Constitution through the appointment of the IGP, the members of the Human Rights Commission and so on.

This violation of the highest law in the land has been condoned by various entities, including the Supreme Court, the Leader of the Opposition and the Speaker of Parliament.

It must be noted that the sabotaging of the 17th Amendment did not start with the present President.

But that process was taken to the next level by the making of extra-constitutional appointments during his term.

If the highest authority in the land does what he pleases, unconstrained by the supreme law, we live in a country that is ruled by a President not by law.

We should not be surprised that law is violated at all levels of the executive.

A simple example that everyone can see is the flagrant abuse of public funds by entities such as the National Lotteries Board to erect patently political hoardings to celebrate the first anniversary of the assumption of power by the President.

If there is no rule of law, the prospects of the MPs who took their oaths as ministers on January 28th are bleak indeed.

Even if they are not summarily discarded like the President's erstwhile allies, it is unlikely that they will be able to do anything meaningful with their portfolios, subject as they will be to the rule of men (namely the President, his siblings and close associates) rather than the rule of law.

So my recommendation is that all persons of goodwill, in Parliament as well as outside, should give priority to either implementing the 17th Amendment fully (including the provisions regarding the Elections Commission), or amending it to a form they can stomach and then implementing the amended Constitution faithfully.

A government that violates its own Constitution will not be trusted by decent investors and partners, let alone by the LTTE, whose agreement at the negotiating table is essential if this cancer of war is to be eliminated from the Sri Lankan body politic.

Such a government should not be trusted by its people either.