March 28, 2007 (LBO) - It seems like a no-brainer: A mobile phone is better than a fixed phone, especially in Sri Lanka. The costs of getting a connection are lower: a new phone and SIM can cost as little as LKR 4,000, while SLTL charges around LKR 20,000 for a fixed connection and its competitors charge around LKR 10,000.

Mobile phones are easy to use. They have built in directories and allow texting, though now these features are now available on the fixed CDMA phones as well.

Calling people instead of places that people are associated with seems obviously better, unless you don’t want to be reached. The whole world seems to think so, with mobile outstripping fixed all over the world, except in North Korea, Myammar and a few other bastions of self-sufficiency and juche (

http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Juche).

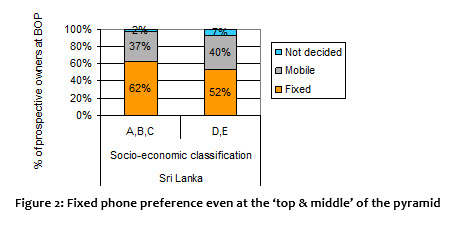

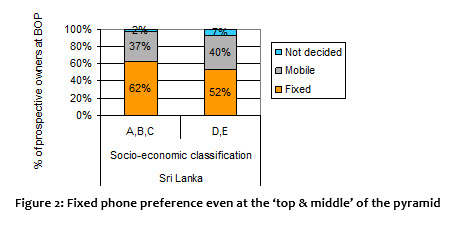

Yet, our people think differently. A recent survey of teleuse at the bottom of the pyramid (teleuse@BOP) by LIRNE

asia showed that a significant number of Sri Lankans in SEC D&E groups (and possibly all Sri Lankans) who plan to get connected in the next two years prefer fixed phones:

In fact, even those in higher SEC groups (A, B and C), what could be termed the ‘top and middle’ of the pyramid, prefer fixed phones.

Receiving Party Pays?

Receiving Party Pays?

An obvious explanation is the Receiving Party Pays (RPP) scheme that Sri Lanka is still stuck on, after other countries have moved on. For example, both India and Pakistan used to require a person who received a call on a mobile to pay for it, but now are in a CPP [calling party pays] scheme that treats mobile and fixed the same.

Twice, the TRC came close to implementing CPP, but twice it backed off. On the second occasion, it was on the novel basis that over 4,000 submissions (many with identical wording) were received opposing the change. The TRC also stated that the decisions to first suspend and then rescind the announced conversion to CPP had nothing to do either with the Parliamentary elections of 2004 (which followed the suspension decision) and the Presidential election of 2005 (which occurred soon after the decision to rescind).

CPP was said to be bad for persons making calls from fixed phones to mobiles. But, mobile users in an RPP scheme were, and still are, paying for calls that they did not originate. And there are lots more mobile users than fixed, now (and there is no election for the TRC to worry about).

Rural fixity?

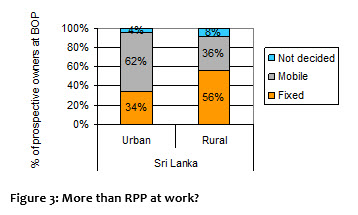

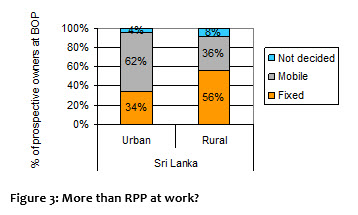

In all the countries surveyed, except the Philippines, people at the BOP in rural areas appeared to favor fixed over mobile, Sri Lanka being the most pronounced. This suggests that something more than unhappiness about RPP may be at work.

This could be possibly explained by the absence of mobile signals and the heavy marketing of CDMA phones in the rural areas. After all, even one of the remotest villages in Sri Lanka, Meemure, today boasts several CDMA connections but had no mobile signal (at least in July 2006).

Mobile males?

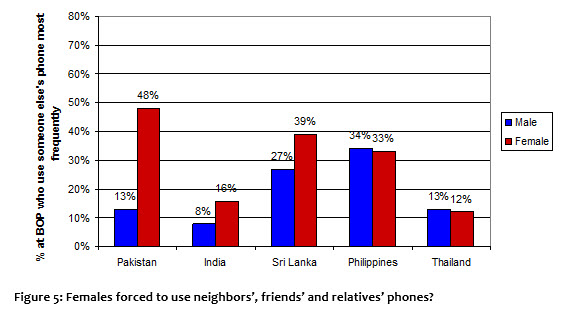

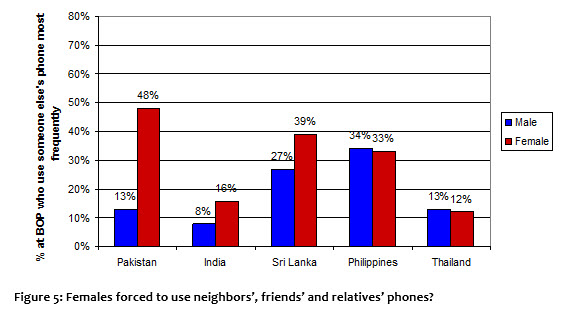

But could it possibly be attributable to family dynamics? It appears that mobiles are used mostly by males, especially at the BOP in South Asia. Our ratio is not as bad as in India or Pakistan, but not as good as in SE Asia:

Women who do not own phones seem to rely on friends and neighbors more than on communication bureaus and similar public facilities:

The hogging of mobile phones by men may be causing women to favor fixed phones which are more likely to be left in the house for everyone to use (though people are known to take CDMA phones around with them in shopping bags).

Not irrational

Not irrational

Therefore, the Sri Lankan preference for fixed phones may not be as irrational as it appears. The suspicion that juche may be catching on among the people of this country is not substantiated by the evidence.

In the eyes of consumers, there is a clear differentiation between mobile and fixed phones.

Mobiles are seen more as personal phones that tend to be monopolized by males and which require payment for incoming calls. The fixed connection, even with CDMA is seen as stable, compared to the mobile connection. Fixed phones are seen as being available for common use and lower cost, especially because of free incoming calls.

As a result, it appears that monopoly power is alive and well in the fixed market. The incumbent SLTL is making excessive profits by applying standard tariffs designed for expensive copper-based connections to CDMA connections which cost as little as USD 30 a line. In its own words,

SLTL is boasting of “a gargantuan growth in its revenue, EBITDA and net profit for the ended financial year.”

While the competitors Suntel and Lanka Bell are not being as rapacious, they too are making excessive profits by sheltering behind the incumbent’s high tariff.

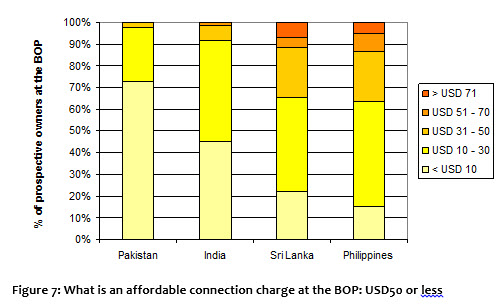

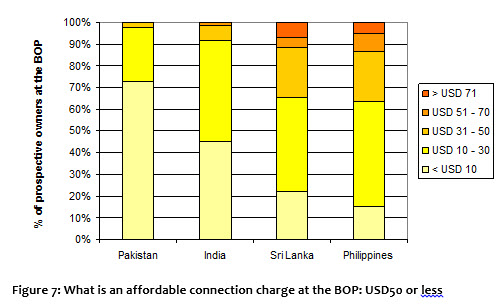

Therefore, it behooves the regulatory agency to bring down the incumbent’s tariff to a level more in line with the drastically reduced costs. If the incumbent is compelled to offer a connection at around LKR 5,000 (USD 50; still way above the cost-per-line), the prices levied by Suntel and Lanka Bell will also have to come down.

They’ll still keep making money; and may even make more than they do now by bringing in more of the ready-and willing-but-cannot-afford:

Of course, the TRC may consider introducing CPP which would make the mobiles more of a substitute for fixed, in which case the current connection charges will cease to be sustainable. We would have real competition and convergence to boot.

And most importantly, the TRC will help make dent in the waiting list of 366,564 and may be even responsible for Sri Lanka pulling ahead of Pakistan in the telecom rankings.

In fact, even those in higher SEC groups (A, B and C), what could be termed the ‘top and middle’ of the pyramid, prefer fixed phones.

In fact, even those in higher SEC groups (A, B and C), what could be termed the ‘top and middle’ of the pyramid, prefer fixed phones.

Receiving Party Pays?

An obvious explanation is the Receiving Party Pays (RPP) scheme that Sri Lanka is still stuck on, after other countries have moved on. For example, both India and Pakistan used to require a person who received a call on a mobile to pay for it, but now are in a CPP [calling party pays] scheme that treats mobile and fixed the same.

Twice, the TRC came close to implementing CPP, but twice it backed off. On the second occasion, it was on the novel basis that over 4,000 submissions (many with identical wording) were received opposing the change. The TRC also stated that the decisions to first suspend and then rescind the announced conversion to CPP had nothing to do either with the Parliamentary elections of 2004 (which followed the suspension decision) and the Presidential election of 2005 (which occurred soon after the decision to rescind).

CPP was said to be bad for persons making calls from fixed phones to mobiles. But, mobile users in an RPP scheme were, and still are, paying for calls that they did not originate. And there are lots more mobile users than fixed, now (and there is no election for the TRC to worry about).

Rural fixity?

In all the countries surveyed, except the Philippines, people at the BOP in rural areas appeared to favor fixed over mobile, Sri Lanka being the most pronounced. This suggests that something more than unhappiness about RPP may be at work.

Receiving Party Pays?

An obvious explanation is the Receiving Party Pays (RPP) scheme that Sri Lanka is still stuck on, after other countries have moved on. For example, both India and Pakistan used to require a person who received a call on a mobile to pay for it, but now are in a CPP [calling party pays] scheme that treats mobile and fixed the same.

Twice, the TRC came close to implementing CPP, but twice it backed off. On the second occasion, it was on the novel basis that over 4,000 submissions (many with identical wording) were received opposing the change. The TRC also stated that the decisions to first suspend and then rescind the announced conversion to CPP had nothing to do either with the Parliamentary elections of 2004 (which followed the suspension decision) and the Presidential election of 2005 (which occurred soon after the decision to rescind).

CPP was said to be bad for persons making calls from fixed phones to mobiles. But, mobile users in an RPP scheme were, and still are, paying for calls that they did not originate. And there are lots more mobile users than fixed, now (and there is no election for the TRC to worry about).

Rural fixity?

In all the countries surveyed, except the Philippines, people at the BOP in rural areas appeared to favor fixed over mobile, Sri Lanka being the most pronounced. This suggests that something more than unhappiness about RPP may be at work.

This could be possibly explained by the absence of mobile signals and the heavy marketing of CDMA phones in the rural areas. After all, even one of the remotest villages in Sri Lanka, Meemure, today boasts several CDMA connections but had no mobile signal (at least in July 2006).

Mobile males?

But could it possibly be attributable to family dynamics? It appears that mobiles are used mostly by males, especially at the BOP in South Asia. Our ratio is not as bad as in India or Pakistan, but not as good as in SE Asia:

This could be possibly explained by the absence of mobile signals and the heavy marketing of CDMA phones in the rural areas. After all, even one of the remotest villages in Sri Lanka, Meemure, today boasts several CDMA connections but had no mobile signal (at least in July 2006).

Mobile males?

But could it possibly be attributable to family dynamics? It appears that mobiles are used mostly by males, especially at the BOP in South Asia. Our ratio is not as bad as in India or Pakistan, but not as good as in SE Asia:

Women who do not own phones seem to rely on friends and neighbors more than on communication bureaus and similar public facilities:

Women who do not own phones seem to rely on friends and neighbors more than on communication bureaus and similar public facilities:

The hogging of mobile phones by men may be causing women to favor fixed phones which are more likely to be left in the house for everyone to use (though people are known to take CDMA phones around with them in shopping bags).

The hogging of mobile phones by men may be causing women to favor fixed phones which are more likely to be left in the house for everyone to use (though people are known to take CDMA phones around with them in shopping bags).

Not irrational

Therefore, the Sri Lankan preference for fixed phones may not be as irrational as it appears. The suspicion that juche may be catching on among the people of this country is not substantiated by the evidence.

In the eyes of consumers, there is a clear differentiation between mobile and fixed phones.

Mobiles are seen more as personal phones that tend to be monopolized by males and which require payment for incoming calls. The fixed connection, even with CDMA is seen as stable, compared to the mobile connection. Fixed phones are seen as being available for common use and lower cost, especially because of free incoming calls.

As a result, it appears that monopoly power is alive and well in the fixed market. The incumbent SLTL is making excessive profits by applying standard tariffs designed for expensive copper-based connections to CDMA connections which cost as little as USD 30 a line. In its own words, SLTL is boasting of “a gargantuan growth in its revenue, EBITDA and net profit for the ended financial year.”

While the competitors Suntel and Lanka Bell are not being as rapacious, they too are making excessive profits by sheltering behind the incumbent’s high tariff.

Therefore, it behooves the regulatory agency to bring down the incumbent’s tariff to a level more in line with the drastically reduced costs. If the incumbent is compelled to offer a connection at around LKR 5,000 (USD 50; still way above the cost-per-line), the prices levied by Suntel and Lanka Bell will also have to come down.

They’ll still keep making money; and may even make more than they do now by bringing in more of the ready-and willing-but-cannot-afford:

Not irrational

Therefore, the Sri Lankan preference for fixed phones may not be as irrational as it appears. The suspicion that juche may be catching on among the people of this country is not substantiated by the evidence.

In the eyes of consumers, there is a clear differentiation between mobile and fixed phones.

Mobiles are seen more as personal phones that tend to be monopolized by males and which require payment for incoming calls. The fixed connection, even with CDMA is seen as stable, compared to the mobile connection. Fixed phones are seen as being available for common use and lower cost, especially because of free incoming calls.

As a result, it appears that monopoly power is alive and well in the fixed market. The incumbent SLTL is making excessive profits by applying standard tariffs designed for expensive copper-based connections to CDMA connections which cost as little as USD 30 a line. In its own words, SLTL is boasting of “a gargantuan growth in its revenue, EBITDA and net profit for the ended financial year.”

While the competitors Suntel and Lanka Bell are not being as rapacious, they too are making excessive profits by sheltering behind the incumbent’s high tariff.

Therefore, it behooves the regulatory agency to bring down the incumbent’s tariff to a level more in line with the drastically reduced costs. If the incumbent is compelled to offer a connection at around LKR 5,000 (USD 50; still way above the cost-per-line), the prices levied by Suntel and Lanka Bell will also have to come down.

They’ll still keep making money; and may even make more than they do now by bringing in more of the ready-and willing-but-cannot-afford:

Of course, the TRC may consider introducing CPP which would make the mobiles more of a substitute for fixed, in which case the current connection charges will cease to be sustainable. We would have real competition and convergence to boot.

And most importantly, the TRC will help make dent in the waiting list of 366,564 and may be even responsible for Sri Lanka pulling ahead of Pakistan in the telecom rankings.

Of course, the TRC may consider introducing CPP which would make the mobiles more of a substitute for fixed, in which case the current connection charges will cease to be sustainable. We would have real competition and convergence to boot.

And most importantly, the TRC will help make dent in the waiting list of 366,564 and may be even responsible for Sri Lanka pulling ahead of Pakistan in the telecom rankings.