By Dr Asanka Wijesinghe and Nilupulee Rathnayake:

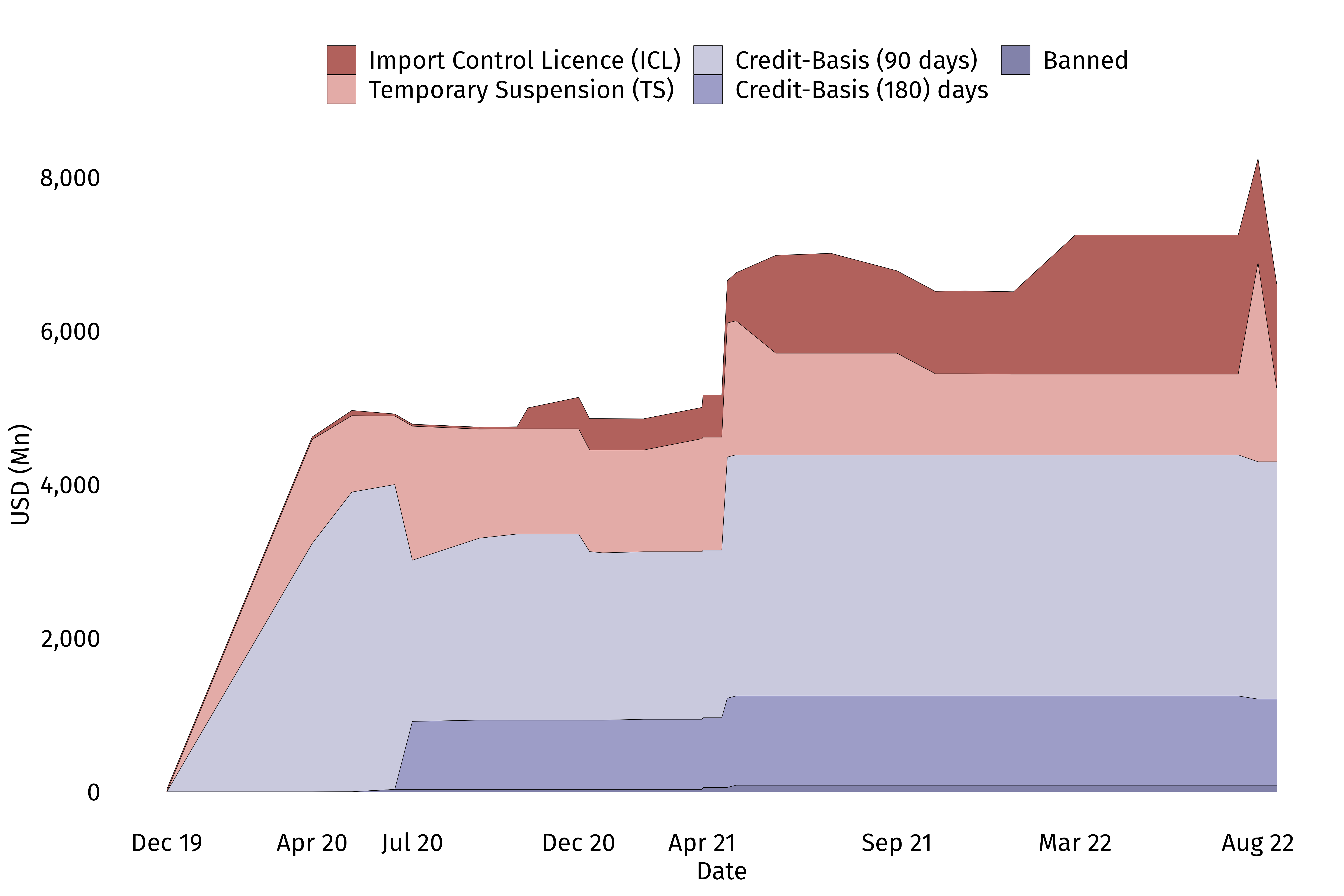

In response to the economic crisis, Sri Lanka implemented import controls that expanded significantly by the end of 2022, accounting for approximately 30% of the country's total import value (Figure 1). The controls affected various categories, including consumption goods (46%), intermediate goods (31%), and capital goods (24%). As Sri Lanka gradually eases these controls, questions arise about the necessity of this strategy and its impact on economic growth.

- Was implementing import controls a necessary strategy or the easiest option available to the government?

- Were import controls applied optimally to limit damaging effects on growth?

- Did they distort incentives, thereby promoting domestic production of substitutable products?

To shed light on these concerns, a comprehensive analysis was conducted using a unique dataset comprising eight waves of import controls. These controls encompassed quantitative and price restrictions at a disaggregated product level using a range of Gazette notifications issued between April 2020 to September 2022.

Figure 1: Coverage of Import Controls from April-2020 to the end of 2022.

Notes: Data compilation was from various import control Gazette notifications. Values used in the study are from 2017, as more recent data on HS-eight digits were unavailable.

Source: Authors’ illustrations

Were Import Controls Necessary? Unravelling the Policy Objectives

The objective behind the successive rounds of controls remains unclear, with the government declaring different goals at different times. These ranged from reducing foreign currency outflows to promoting domestic production as import substitutes. As such, assessing their longer-term impacts in distorting the incentive structures is crucial. Interestingly, implementing import controls may have inadvertently encouraged import substitution, even without a protectionist intent. The complexity of the measures employed, including credit-based requirements, import licenses, suspensions, and bans, highlights the intricacies of controlling imports.

Several hypotheses prevail in determining the government’s import control preferences.

- Sri Lanka’s heavy reliance on imported intermediate and capital goods for domestic consumption and export-oriented production means that these are more likely to be exempted from minimising adverse impacts on domestic production.

- The large agricultural labour force has significant electoral importance, and to gain political support, the government may seize the opportunity to protect domestic food production.

- If import substitution is the goal, the government will prioritise less complex products, which are easily substitutable given resource endowments and technical know-how. Thus, food items, for instance, are more likely to face import controls over highly complex products. It is worth noting that if subsequent rounds of import controls consistently include less complex food products without exemptions, it could indicate an underlying incentive structure that promotes import substitution.

- Even without a protectionist motive, the import control design could inadvertently incentivise import substitution.

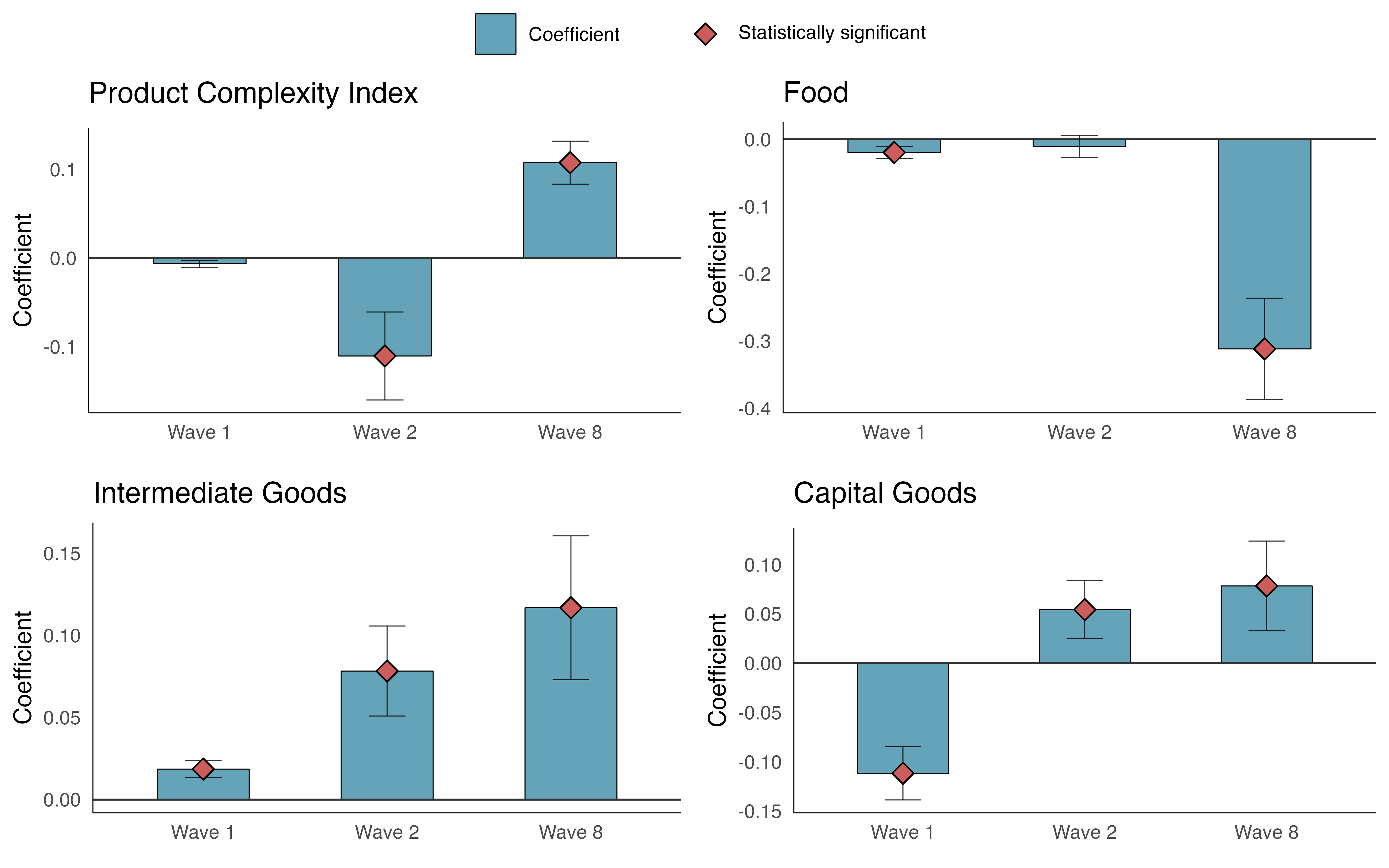

Our analysis revealed that the government’s import control policy preference favoured less complex products, consumer goods, and food items. This unintentionally created an incentive structure for import substitution, even without a protectionist intent. Persistent import controls on food products and low-tech manufacturing products like consumer electronics inflate domestic prices and create opportunities for higher profit margins. As these products are within the set of products that are easily substitutable for a country like Sri Lanka, which has a comparative advantage in low-tech manufacturing and a significant labour force in agriculture, import substitution might happen even without a policy intent.

The quantitative analysis identified eight waves of import controls, which tightened over time and increased in coverage. The government's targeting of food products, consumption goods, and less complex items was not always successful, particularly in the later waves of import controls. This can be attributed to a shrinking choice set available as control measures progressed. In some import control waves, the government extended import controls to encompass more intermediate and capital goods.

The process of import substitution typically follows a sequential pattern, starting with substituting easily replaceable products before moving on to more complex ones. Therefore, irrespective of the policy objective, the distortions introduced to the incentive structure align with observations from import substitution scenarios seen in countries like Sri Lanka.

Table 1: Top five industries with the highest and lowest protection, which are among the top imports.

| Industries with Highest Protection Levels by Import Value | Industries with Lowest Protection Levels by Import Value | |||

| Industry | Protection Coverage | Industry | Protection Coverage | |

| Communication equipment | 100.0 | Manufacture of knitted and crocheted fabrics | 0.0 | |

| Electric motors, generators, transformers and electricity distribution apparatus | 91.4 | Weaving of textiles | 0.0 | |

| Dairy products | 90.0 | Manufacture of other textiles | 0.0 | |

| Manufacture of basic precious and other non-ferrous metals | 90.0 | Manufacture of pulp, paper and paperboard | 0.1 | |

| Manufacture of pharmaceuticals, medicinal chemical and botanical products | 89.1 | Extraction of crude petroleum | 0.2 |

Source: Authors’ calculation

Recommendations for Prioritising Import Control Revisions

As Sri Lanka gradually eases the import controls implemented during the economic crisis, it becomes crucial to prioritise the revision process. The deciding factors may be influenced by lobbying from industries reliant on restricted imports and feedback from industry and consumers. Our analysis suggests that revisions appear to prioritise intermediate and exempted food products, reflecting a policy preference for exempting intermediate imports (Figure 2).

Figure 2: Variation in the Likelihood of a Product being Removed from Import Controls during Revisions

Notes: Intermediate products were more likely to be removed from import controls in each wave, while consumption goods were less likely to be deleted. Food products were less likely to be removed from import controls than non-food items.

Source: Authors’ estimates

To foster innovation and enable participation in global value chains, it is economically sensible to phase out import controls on intermediate goods. However, revisions should also target consumption goods, including food. Import controls inflate domestic prices, leading to the production of less complex consumer goods and food items for domestic consumption. This diverts resources away from export industries, impeding the country's growth in the vital export sector.

Revisiting import controls on food products is particularly important due to their impact on urban and suburban households. These controls exacerbate food costs and shortages, burdening households, especially those with low incomes. More damagingly though, the distortion in incentives (the import-substitution incentive structure) perpetuates labour movement and retention in the agriculture sector.

More details on this study can be found in Wijesinghe, A., Yogarajah C., and Rathnayake N., (forthcoming) “Import Controls in Sri Lanka: Political Preference and Incentive Distortions”, International Economic Series, Institute of Policy Studies of Sri Lanka. Colombo.

Asanka Wijesinghe is a Research Fellow at IPS with research interests in macroeconomic policy, international trade, labour and health economics. He holds a BSc in Agricultural Technology and Management from the University of Peradeniya, an MS in Agribusiness and Applied Economics from North Dakota State University, and an MS and PhD in Agricultural, Environmental and Development Economics from The Ohio State University. (Talk with Asanka - asanka@ips.lk)

Nilupulee Rathnayake is a Research Assistant working on Macro, Trade and Competitiveness research at IPS. She holds an MSc in Development Economics from the University of Nottingham, United Kingdom, and a BA in Economics from the University of Colombo, Sri Lanka. (Talk with Nilupulee - nilupulee@ips.lk)