Feb 21, 2006 (LBO) -- In some discussions in 2002-04 when the government was interested in a bridge cum utility conduit over the Palk Strait (the now forgotten "Hanuman Bridge"), someone expressed concern that it would make illegal immigration to Sri Lanka easier. My reaction was that I wished that were true.

In the 1960s, in the halcyon days when we prided ourselves in having a ceremonial army and a Navy with one ship, one of the duties of the armed forces was to guard the shores of Sri Lanka against "kallathonis." These were illegal immigrants from India.

Those who know the meaning of this term nowadays are generally over 45. The term has gone into desuetude along with the phenomenon. Today we mobilize the police and sometimes even the army to prevent people from leaving Sri Lanka in multi-day fishing craft, not the other way around.

Why did I wish for the return of the kallathonis? Because it would be proof that Sri Lanka is a good place to live, not to leave.

Voting with your feet

According to Index Mundi

(http://www.indexmundi.com/g/r.aspx?c=in&v=27), Sri Lanka has a net migration rate of -1.27 (a net loss of 1.27 people per 1000 population). Bangladesh has a lower level (-0.69) as does India (-0.07). Only Pakistan, among our South Asian neighbors, loses more people per capita (-1.67). In the region, only Afghanistan has a high positive rate of 21.43, suggesting a massive movement of displaced people back into the country after the end of the successive wars.

Qatar, Kuwait and Singapore have high in-migration rates of 15.17, 14.96 and 10.3 respectively, possibly including temporary movements of workers. Botswana, one of the richest countries in Africa, attracts over six new migrants per 1000 population. Canada has the highest in-migration rate among large economies with a rate of 5.9.

Whatever be the precision of these numbers (does anyone know precisely how many people of what nationalities left the shores of Sri Lanka on multi-day fishing craft?), the general conclusion that Sri Lanka has a high out-migration rate is unsurprising.

Behind the net migration numbers are millions of individual stories of heartbreaking decisions: of an established professional filing an application at the Australian High Commission while agonizing over the care of his parents; of an unemployed youth borrowing money at usurious rates to pay a people smuggler for passage to Italy; of a young woman marrying a much older European to seek a better life; of families being split apart for the sake of the family.

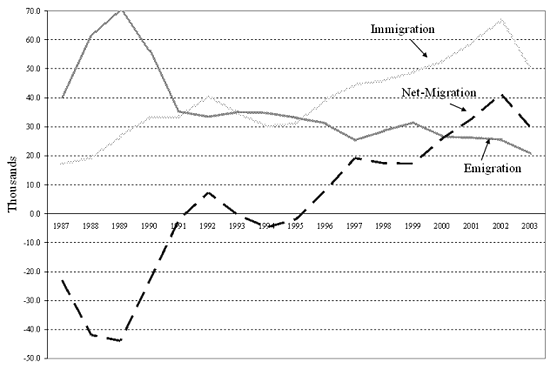

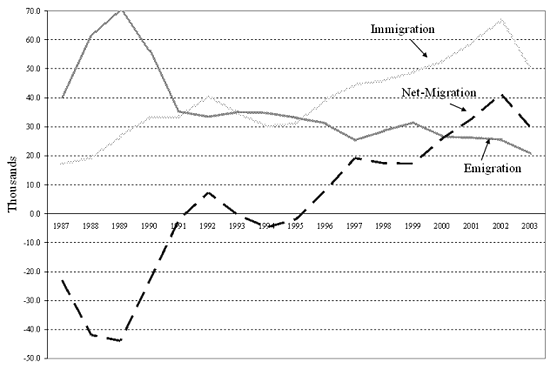

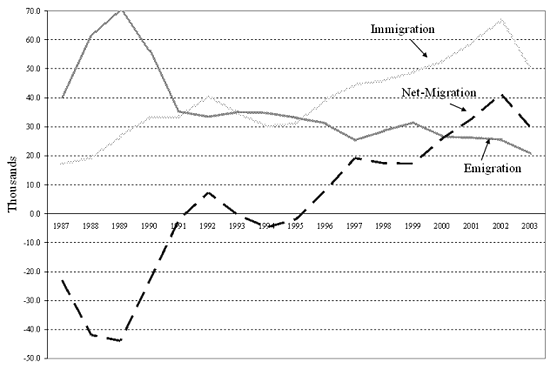

Certain events such as Black July in 1983, the start of the JVP's second insurrection in 1987 and the start of the second Eelam War 1990, cause major shifts in the migration patterns, but in the end, migration is the aggregate of millions of individual assessments of the costs and benefits of continuing to live in Sri Lanka.

What could have been

For decades, Ireland lost its young in large numbers to migration. But since the 1990s it has experienced high in-migration, the current rank being 4.93 per 1000 population, higher than Australia (3.91), New Zealand (3.83) and the United States (3.31).

When Ireland was pursuing inward-looking economic policies and the economy was in the doldrums, its young people left in large numbers for the United States, the UK and other countries. Even today an estimated 3 million Irish citizens (among them, 1.2 million born in Ireland) live outside the country.

After adopting investment-friendly policies (including pioneering business process outsourcing), Ireland experienced sustained and rapid economic growth and high demand for labor. From the being called the "sick man of Europe," Ireland has now achieved the highest per capita GDP after Luxembourg in Europe. The Irish who emigrated started coming back and additional workers from the European Union as well as other countries started to enter on work permits.

Source: Ruhs,

Martin (2004, October). Ireland: A crash course in immigration policy,

Migration Information Source

http://www.migrationinformation.org/Profiles/display.cfm?id=260

So people leave when the economy is mismanaged and prospects for their families are bad. They also leave when there is war. Sri Lanka, since Independence has satisfied one or both conditions, with things getting really bad on the economic front in 1970-1977 and mass migration being accelerated by the pogrom of July 1983. The open society since 1977 allowed ordinary people to see there were choices. Migration became an option for them also, not just the Burghers and the upper-class Sinhalese and Tamils who had started voting with their feet since the 1950s.

According to Index Mundi, net migration has been decreasing in Sri Lanka over the past five years from -1.43 in 2001 to -1.27 in 2005. I take this as a good sign. Will the trend continue? The answer lies in the efficacy of the Mahinda economic policies and success of the Geneva talks.

When kallathoni enters the lexicon again and multi-day fishing craft are seen solely as fishing vessels, someone should throw a party. If I am still in the country, I'll be sure to come.

-Rohan Samarajiva:

samarajiva@lirne.net