By Wimal Nanayakkara:

High levels of inequality impede sustainable growth and development of a country. Sri Lanka made impressive strides to reach an upper middle-income country (UMIC) status in July 2019, only to slip back a year later. The COVID-19 crisis, amid growing inequities, is likely to make the task of regaining UMIC status even harder.

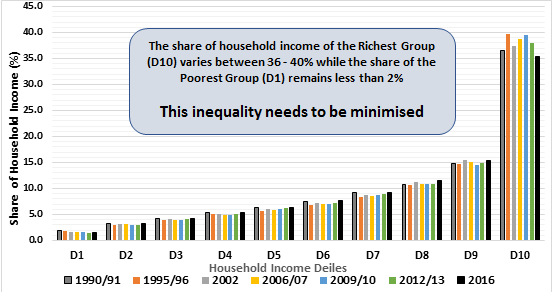

The present health pandemic is exerting significant adverse impacts across many sectors of the Sri Lankan economy. In particular, economic activities related to tourism and travel and associated activities of hotels and restaurants are struggling. So too are apparel exporters, small/medium-scale enterprises, and construction related activities. Many of these economic activities are dominated by the self-employed and daily wage earners. COVID-19 in particular has been especially harsh on the poor, running the risk of widening existing socio-economic inequalities. Indeed, any further increase in income inequality, which is already high in Sri Lanka (Figure 1), could lead to social unrest.

This blog highlights the main sectors and social groups that are adversely affected, and explains the need for inclusive economic growth (IEG) post-COVID-19 for Sri Lanka to emerge as a peaceful and developed country.

Figure 1 - Share of Total Household Income by Household Income Deciles – 1990/91 to 2016

Source: Prepared by the Author based on Household Income and Expenditure Surveys (1990/91 to 2016), Department of Census and Statistics.

UMIC Status in 2019

Although Sri Lanka achieved UMIC status in July 2019 based on its gross national income (GNI) of USD 4060 per capita in 2018, the country was at the lower end of the threshold for UMICs. As predicted in an earlier blog, Sri Lanka slipped back to a lower-middle income country (LMIC) in July 2020. This was due to (1) the revision of the threshold for UMICs by the World Bank in 2020 and (2) Sri Lanka’s poor economic performance in 2019.

A number of facts showed that Sri Lanka was not ready for UMIC status in 2019, such as declining gross domestic product (GDP) growth rates and relatively high levels of inequality. Sri Lanka’s GDP had been declining from 5% in 2015 to 3.2% in 2018 and to just 2.6%, after the terror attacks in April 2019, and the country’s GNI dropped to USD 4020 per capita in 2019, pushing it back to LMIC status.

Although Sri Lanka managed to bring down poverty to a satisfactory level as per its national poverty headcount ratio, according to UMIC standards, more than 40% of the country’s population would be in poverty. This is based on USD 5.50 per person a day, the global poverty line for UMICs.

Another major issue is persistently high income inequality. When such a large proportion of the country’s population is in poverty, with high income inequality, is it possible to consider Sri Lanka a UMIC? The policies implemented thus far have failed to reduce the gap between rich and poor. This gap could further widen due to the adverse effects of COVID-19, which impacts the poor disproportionately.

Setbacks and Opportunities

Following are some of the key sectors of the economy affected by COVID-19 which were earning much needed foreign exchange for the country.

Tourism: When the sector was gradually recovering after the April 2019 Easter Attacks, COVID-19 struck the country in March 2020 bringing the tourist arrivals to zero thereby affecting the livelihoods of more than 400,000 Sri Lankans who directly depend on the industry. The number of those indirectly affected could be as high as 1.5 million.

Migrant Workers: By mid-October 2020, over 54,000 migrant workers had returned and around 43,000 were still awaiting repatriation. However, there is an increase of 3.9% in worker remittances from January to November 2020 (USD 6.291 million), compared to the same period in 2019 (USD 6052 million). Encouragingly and defying expectations, remittances hit a historic high of USD 813 million for December 2020 reflecting a 22.2% year-on-year growth compared to December 2019. Therefore, the main concerns related to this sector at present would be the reintegration of the returnees and survival of the families who depend on remittances from their loved ones.

Exports: Due to the combined efforts of the government and the exporters, the overall export earnings which declined from USD 966 million in February 2020 to USD 282.3 million in April, managed to make a ‘V’ shaped recovery reaching USD 1.09 billion by July 2020 and then to remain around USD 1 billion until September 2020. Unfortunately, the second wave of COVID-19 has pushed export earning down to USD 848 million in October and then to 819 million in November. The EDB’s revised target for 2020 is USD 13.4 billion, out of which 88.5% was achieved by November.

The remarkable performance in the export sector up to September 2020 clearly shows that possibilities exist for Sri Lanka to recover and move forward with new thinking, efficient planning, swift action and collaboration between public and private sector agencies. It is noteworthy that the government has given the highest priority to develop this sector which would create employment and economic opportunities at all levels, while earning much needed foreign exchange, at this difficult juncture.

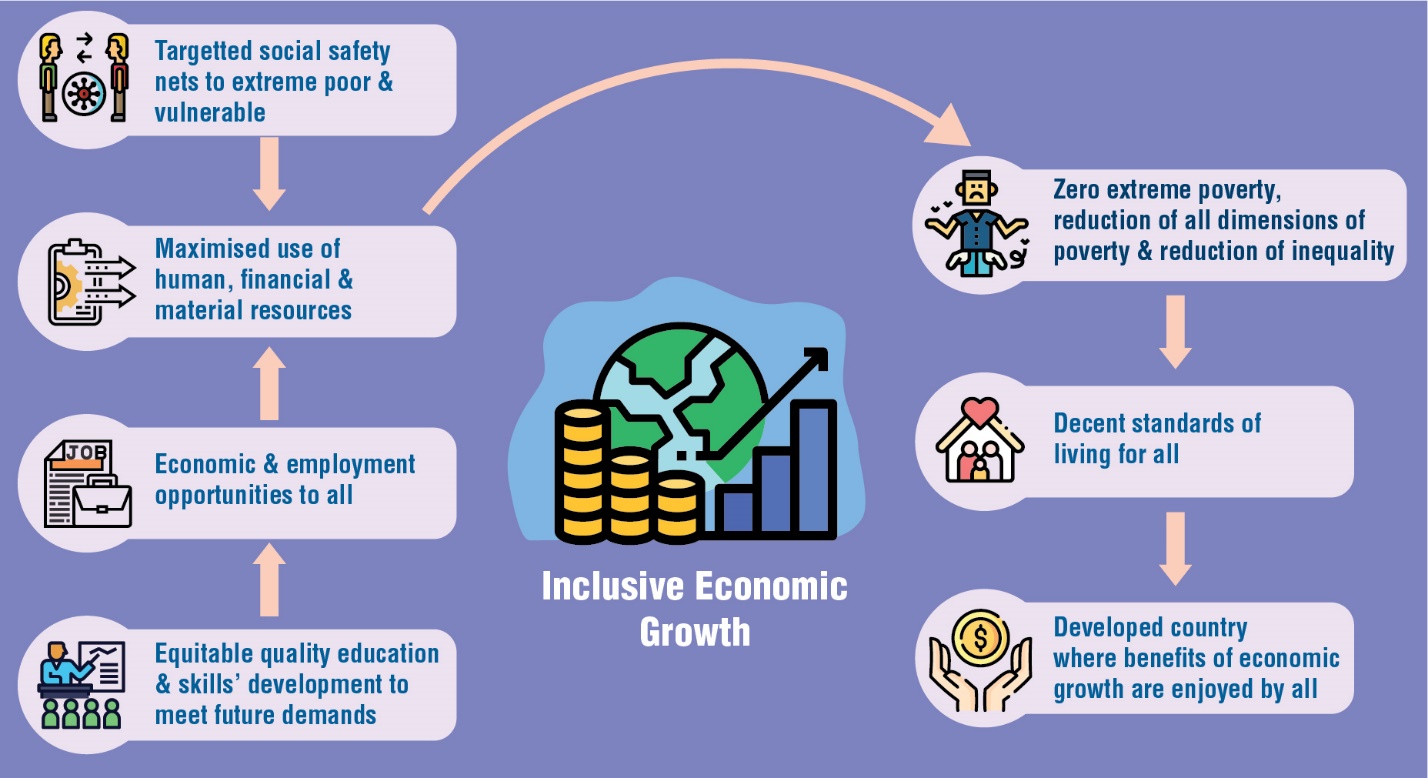

Inclusive Economic Growth

For Sri Lanka to emerge as a peaceful and developed country, economic growth needs to be inclusive, though it is a significant challenge. Thus, any strategy for post-COVID-19 recovery should ensure IEG that would create economic and employment opportunities for all, including especially the poor and the vulnerable. For Sri Lanka’s persistent high income inequality to be bridged, the following categories of persons require special attention: (1) self-employed; (2) daily wage earners; (3) returning migrant workers and their families; (4) tourism sector workers (5) socio-economic groups with a high incidence of poverty and (6) all others whose livelihoods have been hit.

Pro-poor and inclusive growth strategies should also include:

(1) coordinated and targetted social safety nets;

(2) equitable, quality education and skills development;

(3) agricultural sector development, including modernisation and guidance to increase productivity; ethical marketing facilities; and minimising post-harvest wastage; and

(4) increased female labour force participation, by creating decent employment opportunities closer to where they live, permitting working from home, flexible working hours, etc.

Wimal Nanayakkara is a Senior Visiting Fellow at the Institute of Policy Studies of Sri Lanka (IPS) with research interests in poverty, and is a specialist in sampling. He was previously engaged at the Department of Census and Statistics, where he functioned as the Director General for 12 years. He received his BSc in Mathematics and Physics from the University of Peradeniya and holds a Postgraduate Diploma in Applied Statistics from the University of Reading, UK. (Talk to Wimal - wimal@ips.lk)